A World of Women: Celebrating the WOW Café

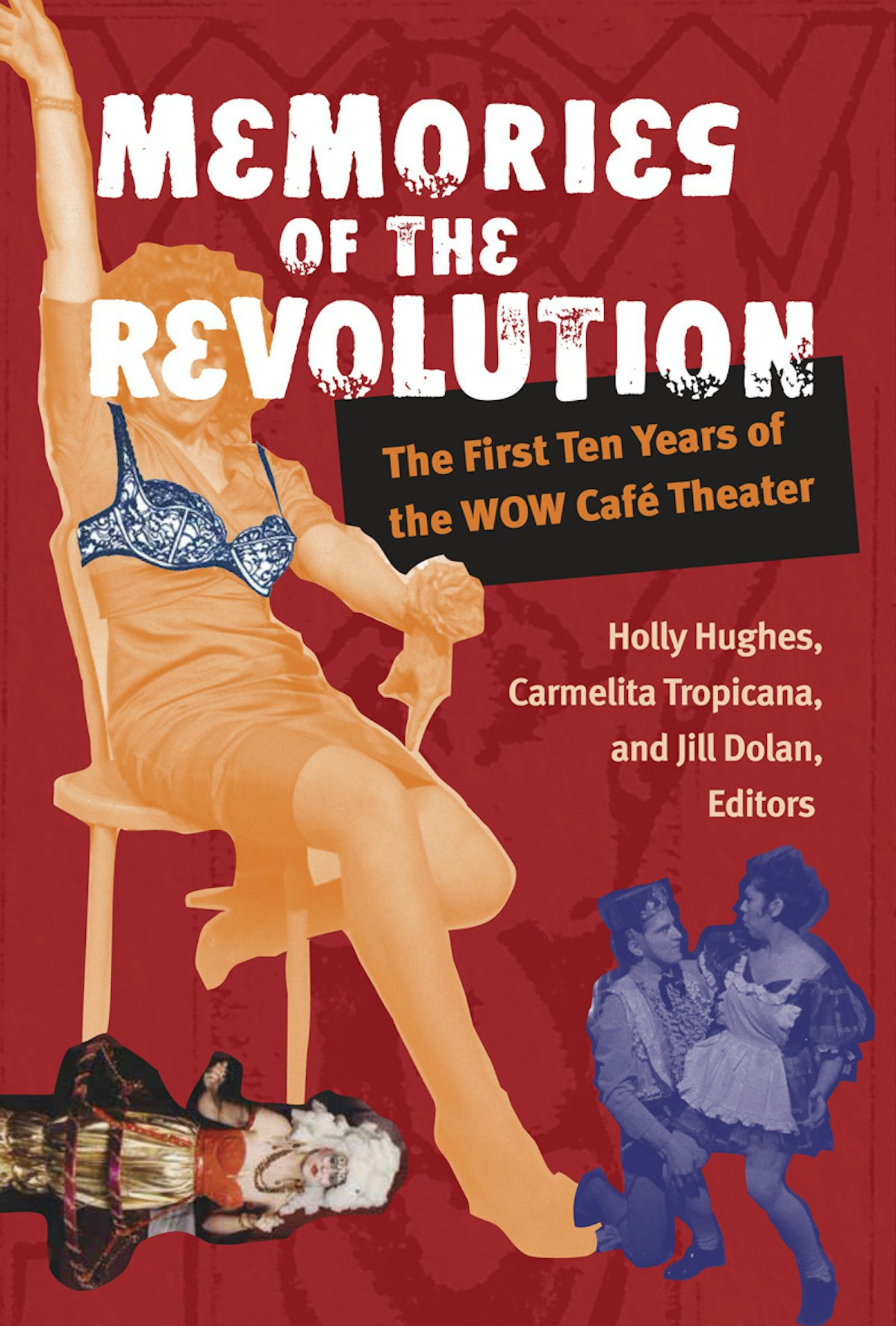

Memories of the Revolution: The First Ten Years of the WOW Café Theater, co-edited by Stamps and School of Music, Theatre & Dance Professor Holly Hughes, was a finalist for the 2016 Lambda Literary Award in the LGBT Anthology category. The book was published by the University of Michigan Press, and Hughes' co-editors are Carmelita Tropicana and Jill Dolan.

The following article, by Merryn Johns, first appeared in the March/April issue of Curve Magazine and is reprinted with permission.

Two decades ago, when I was researching lesbian theater, during my student days in Australia, I scoured just about every academic publication I could get my hands on for evidence of contemporary lesbian plays.

Nestling within the rarely thumbed pages of a few dusty theater journals that had made it all the way from the States to Sydney, I discovered photos and excerpts from plays with titles such as The Lady Dick and The Well of Horniness — written and performed by women at an enticing establishment called the WOW Café. Other WOW titles, I was delighted to learn, included Voyage to Lesbos, Tart City, and Paradykes Lost.

The WOW Café was (and still is) a feminist theater space in Manhattan's East Village. It grew out of a 1980 feminist theater festival whose proponents wanted a permanent home for their creativity. The first women of WOW, like Lois Weaver and Peggy Shaw, who were veterans of international avant-garde performance, were inspired by the counterculture of the 1960s to foster a lesbian-feminist theater practice. Their vision was made a reality with the help of a number of others, including Holly Hughes and Carmelita Tropicana, who have now published Memories of the Revolution (co-edited with an academic, Jill Dolan) to document the first decade of WOW. This book contains valuable memorabilia and texts — photographs, flyers, play scripts — as well as interviews with the key thespians in the group, including Tropicana, Hughes, Weaver and Shaw, the illustrious Eileen Myles, Lisa Kron and her Five Lesbian Brothers, and other women you may or may not have heard of.

If you were not a theater academic like me, or a resident of downtown NYC in the 1980s and '90s, you could be forgiven for never having heard of WOW at all, because this creative oasis — a paradise of playwriting and acting established by a group of daring dykes — went almost undetected by mainstream tastemakers. And yet every lesbian who cares about culture should care about WOW.

As a student of playwriting I became a fan, especially of Holly Hughes's hilarious and scandalously titled works. I followed her career from her experience as a political pariah, one of the “NEA Four” (she was one of four performance artists whose grants from the U.S. government's National Endowment for the Arts were rescinded by NEA Chairman John Frohnmayer even after they'd been approved, sparking the “culture wars” of the 1990s), to her influential autobiographical solo work, Clit Notes, in which she embodies herself and all the folks who have helped shape her as a lesbian.

Over the years, I interviewed Hughes, attended her performances, and kept in touch, most recently for the release of this new book. While she has held a professorship at the University of Michigan for the past 14 years, and is very committed to “the activism of teaching,” her role as a founder of the WOW Café, and as one of its key performance artists, is still at the core of her work.

From its beginnings, WOW operated as a collective, and it was important to Hughes and Tropicana that Memories of the Revolution “give the artists who were involved with that period of WOW a voice,” says Hughes. “We also felt that Downtown New York cultural history was getting written, but women and lesbians particularly were not a part of it. The book was part of an impetus to make sure it's not completely forgotten.”

Those involved with WOW are helping to keep the flame alive. When I interviewed Lisa Kron last year about her Tony Award–winning hit Fun Home, she credited much of her success to what she learned from the women at the WOW Café. And Eileen Myles, who was at the original WOW Festival and supported the WOW Café, believed in it as an anti-patriarchal laboratory. In Memories of the Revolution, she says that WOW was “the preeminent theater space of its time” and “produced decades of dangerous and vital women,” simply because it focused on diverting the creative process that women lavish on men and children onto each other instead.

This woman-on-woman aesthetic appealed to a young Holly Hughes, who had moved to New York in 1979 to become a part of the Feminist Art Institute, which was started by the Heresies Collective. “The women of Heresies decided that the next step in their feminist organizing was to create their own art educational institution and change the way that art education happened,” recalls Hughes. “I was part of that first cohort, and it was an incredible experience. But no one was getting paid, so it wasn't sustainable. But it was a very transformative experience for me — consciousness-raising was the tool of art-making, and content led form. I remember hearing the teachers say, ‘I'm not going to teach you how to make a good photograph. If you want to make a good photograph, read some books, go to some photo shows… You have to learn what to say.' And a lot of what women wanted to say was just so taboo.”

Three years later, when Hughes joined WOW, where she began acting with Lois Weaver, this ethos was even more pronounced. Weaver believed that “anybody could act, could perform, could tell stories — anybody could do this, you didn't need any preparation.” Hughes sees a continuum from her early performance work through her teaching today. “I'm really interested in what the students want, uncovering their desire, their trauma, having them put it in a larger political analysis.” So much of what happens in school, says Hughes, is about learning technique. “But you can have technique and still not have anything worth saying, looking at, reading, or listening to. For women, for people of color, for immigrants, for queer people — connecting what they want to say, and uncovering what [they] want to say and making it valid is huge.”

Award-winning Cuban-American actor Carmelita Tropicana (real name Alina Troyano), a longtime WOW member and a co-editor of Memories of the Revolution, said in a 1984 group interview at WOW that the work there was “not Serious Theater. We take it lightly.” Indeed, it was hilarious and yet somehow revelatory. Madeleine Olnek, for example, wrote the funny-yet-political Codependent Lesbian Space Alien Seeks Same while at WOW. “[T]hese were the theater people who were ‘like’ me,” says Eileen Myles, who saw her first drag performances at WOW, took part, and even stood naked wearing a dildo in front of an audience. For the record, this audience usually consisted of other lesbians and their friends. Since these shows were not ever reviewed by The New York Times, or even the Village Voice, there was no disapproving bridge-and-tunnel crowd, and only occasionally were there men or straight spectators. WOW was a lovely lesbian bubble, a safe space inside which artistic risks could be taken.

“Of course, I think if any of us had managed to be male, we would've gotten not just more mainstream recognition,” says Hughes, “but WOW might be cited and talked about in the way that Café Cino is — as this important place where so many people worked and made exciting work. And even if the work at WOW wasn't always perfect, there was a great sense of excitement and creative churn. There were spectacular failures, but then next week there'd be another show. It was about making work, not trying to evaluate it to try to make a box office hit.”

One of the most wonderful things about WOW was its assumption that there was an identifiable lesbian sense of humor, a lesbian aesthetic, and a lesbian language, which was most often dripping with desire and satire. Stitched together from Gothic novels, melodrama, radio serials, film noir, pulp fiction, fairy tales, even Gilligan's Island, it was as though WOW's little black box theater space was a virtual Pandora's box containing all the evils of popular culture, and girls were allowed to play with whatever they found inside.

“We had a critical mass of weirdos at WOW,” recalls Hughes. “We were each others' audience. You could be wrong, you could make bad stuff, and still come back. You could make offensive stuff and still come back. In that period, people were campy and funny. We were the first generation who grew up with television — and with television of the 1950s, which was very normative — and we were rebelling against that. And with '60s TV, with all these goofball comedies that kind of shaped us.

“We didn't try to be for all lesbians, and I think that was very smart. We just spoke for us. You make the work that is important to you. It was a small audience, it was easy to fill, and other people weren't going to come: You pleased yourself, and that's such a radical thing for a woman to do.”

Today, says Hughes, so many opportunities for women “are nipped in the bud.” While she has always been supportive of and influenced by gay male creativity, she feels there's a “huge gap” between queer men and women in the theater. “The sexism is undeniable,” she says, and as a teacher, she sees this gap begin early: Her classes are bursting with talented women, she says, but it's usually “a couple of white cisgender guys, who have, as far as I can tell, no self-doubt” who go on to have actual artistic careers. Her female students, albeit talented, seem to have “anchors attached to their feet…Not very many women feel confident, or they second guess their desire to make art.”

Back when WOW started, New York was less expensive to live in, and folks were not constantly plugged into technology. There was time and energy left over at the end of the working day to meet and to make art — or to go see it. While all the pressures that make a counterculture necessary are still with us — bigotry, sexism, homophobia, racism, and gross wealth inequities — our private economic pressures are worse than ever, leaving us little time to create activist art. Nevertheless, Hughes continues to value the idea of the collective. “It's good to have a group, to have your entourage, your posse — not just for sharing expensive rent but to kind of have somebody to laugh at your jokes, to tell you that you can do better, whatever it is. To have an insulating hemisphere against a world that's still kind of toxic.”

But if you're going to start your own lesbian collective, Hughes has some thoughts. “I think the demands placed on women's organizations are ridiculous. ‘Lesbian’ doesn't represent all that I am, either, but it represents an important part of my desire. So the demand that you're going to create an organization or an institution that is completely going to represent all of you is, I think, ridiculous.”

Hughes, like her wife, the LGBT historian Esther Newton, author of Mother Camp and My Butch Career, is not eager to throw out the word ‘lesbian’ and replace it with ‘queer’ for the sake of appearing more inclusive. “In some ways, ‘queer’ functions like ‘gay’ did. ‘Gay’ came in to replace ‘homosexual,’ and it was going to be radical and inclusive just in the way that we talk about ‘queer.’ And then we discovered, in practice, that it became all [or mostly all] white men, and there were always different rationales for why women weren't included and why it was white.”

To many older lesbians, including Hughes, the ongoing critiquing of the word ‘lesbian’ is “part of the damage of sexism,” which leads us perhaps to privilege, or defer to, any other gender expression over our own. “I am very committed to being trans inclusive,” says Hughes, who actively assists students who are in transition, “but I'm concerned about demanding that our history have a kind of perfection. As an artist you need to reference earlier generations, whereas a lot of lesbians now are saying, ‘I'm not a lesbian,’ which is fine — identities shift. But a lot of people have a lack of information, or misinformation, about the very recent past.”

To make assumptions about lesbian history, or to elide lesbian identity in favor of today's labels, is problematic: “It's bad when you're so self-critical that you erase your own history and don't value it. You're participating in your own future erasure, I think,” says Hughes. Which is why Memories of the Revolution is so important. This is what a lesbian collective looked like 35 years ago: safe, inclusive, sexy, fun. A lot of discussion went into how to make WOW more racially diverse, and different strategies were attempted, says Hughes, sometimes effectively, sometimes not. “Thirty-five years later, WOW is a lot more integrated,” says Hughes. A button on its website encourages inclusiveness: “Any woman and/or transgender person is welcome to get involved.”

Even as WOW celebrates its 35th year and appears to be going strong on East 4th Street — events for 2016 have so far included acoustic music, choreography, art, burlesque, and “porch sitting” hosted by founders Weaver and Shaw — fundraising efforts are underway to ensure that this non-hierarchical, trans-inclusive, lesbian-feminist theater collective continues. Visit the website. Make a donation. Buy Memories of the Revolution. Drop in on a Tuesday, which is when the collective meets. Attend a performance. Discover, as Jill Dolan writes in her introduction, “how a scrappy theatre collective that began as a social club where who you were dating was as important (if not more) than the size of your role grew into a laboratory for experimentation that had a lasting impact on future generations of theatre makers and critics.”

More at: www.wowcafe.org.

Article by Merryn Johns