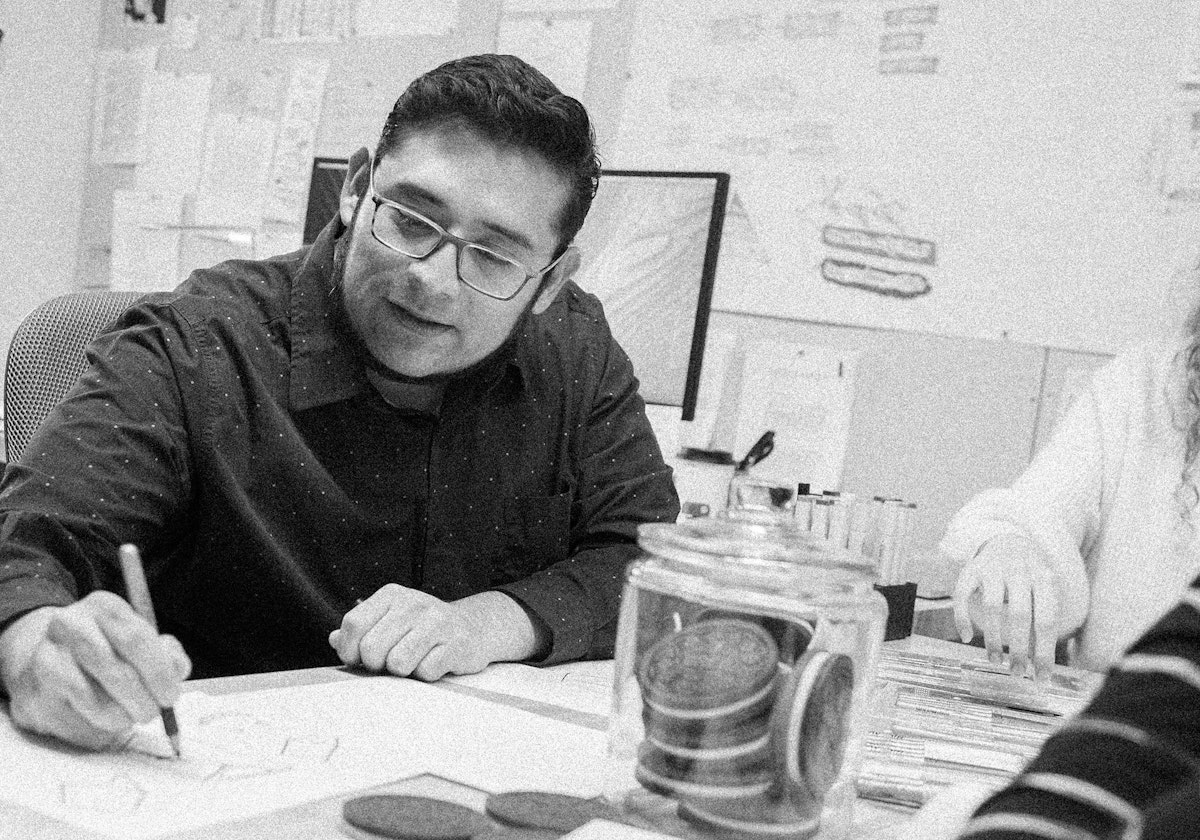

Omar Sosa-Tzec on Delight, Design, and “The Good Life”

Fresh on the heels of completing a Ph.D. in Informatics (Human-Computer Interaction Design) from Indiana University, Assistant Professor Omar Sosa-Tzec joined the Stamps School faculty in Fall 2017. A designer and researcher, Sosa-Tzec believes that product design can help people become active, eager participants in their own health and wellbeing.

In a recent M-Cube funded project undertaken with U-M Professors Rogério Meireles Pinto (School of Social Work) and Shervin Assari (Psychiatry and Public Health), Sosa Tzec and his team researched ways that product design can support self-care for people living with conditions in communities of color and other marginalized populations.

Leveraging the six principles of delight — defined by Sosa-Tzec as engagement, surprise, liveliness, cuteness, serendipity, and reassurance — these products illustrate the role that design can play in shaping human experience. “I’m interested in how design delight shapes reality,” Sosa-Tzec says. “How can it lead us to live the good life?”

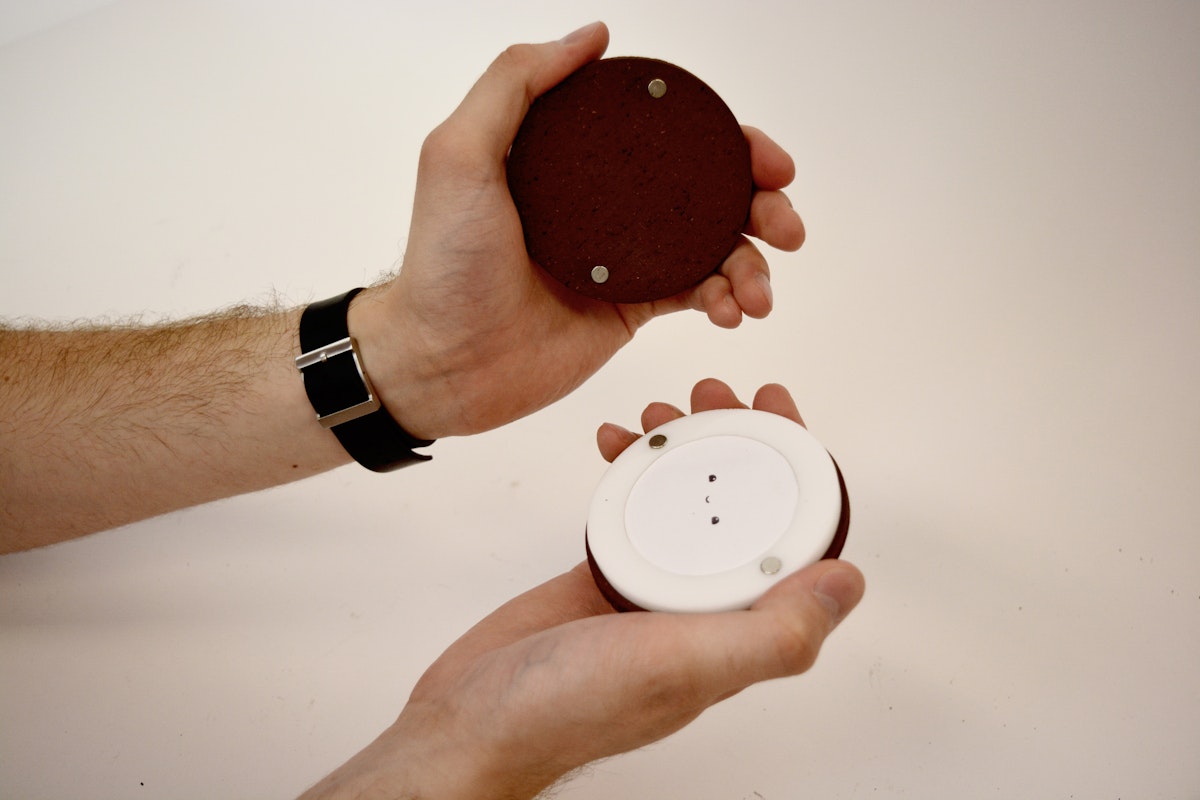

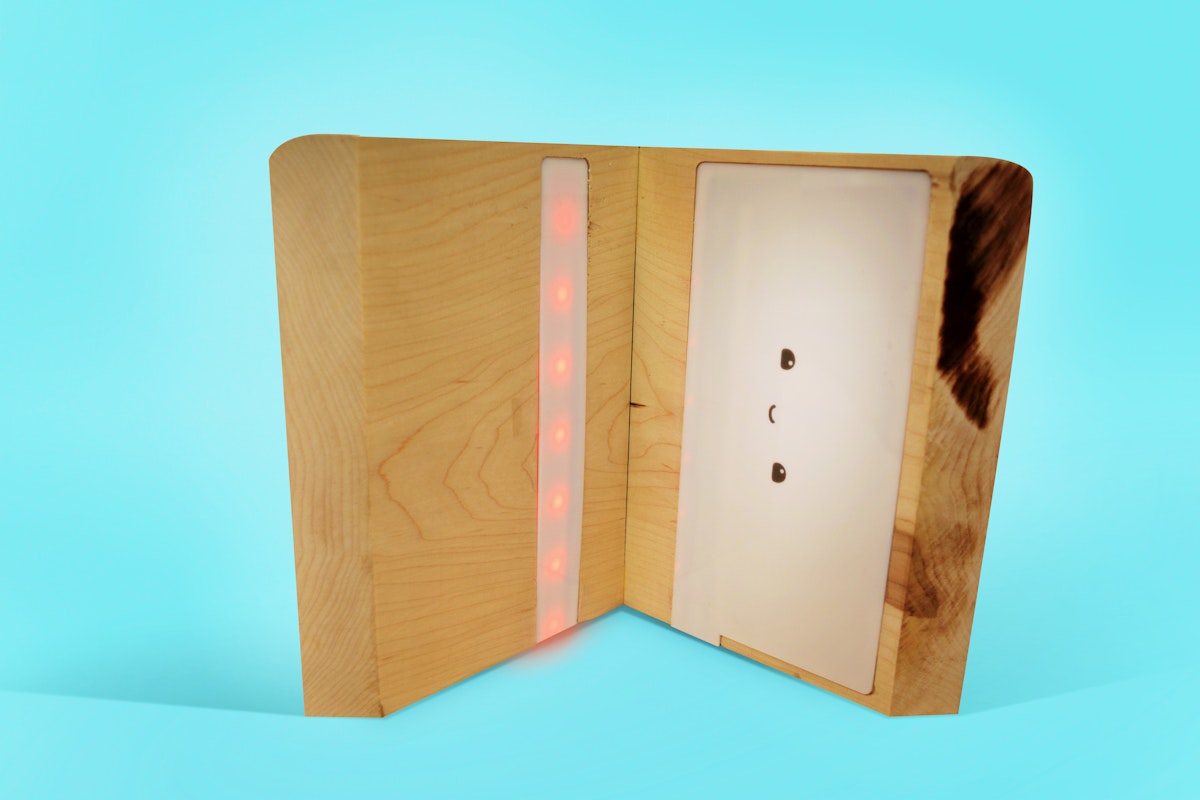

With his multidisciplinary M-Cubed team, which includes U-M undergraduate and graduate students, Sosa Tzec created products that he lovingly calls “delightful companions for well-being.” Companions included fuzzy, tactile blankets to cozy up with after a stressful day; an interactive bookshelf to help foster a culture of reading; a motivational cookie jar filled with positive messages to cherish or share; and cute pill-cases to promote medication adherence.

While it is a common assumption that creative solutions are the result of intuition alone, many 21st century design teams such as Sosa Tzec’s employ a rigorous “research-through-design” (RtD) process to arrive at a prototype. In the RtD model, research is conducted through the design process. A draft of the product is created, evaluated, and tweaked in an iterative fashion, revealing new knowledge along the way — and making the prototype better for the effort. The prototypes that result from the RtD process are not intended to function as a universal solution or for mass production. Rather, they represent the embodied knowledge about how the designer understands the situation and the possible lines of action to address the challenge at hand. Products made through the RtD process as part of a research team are the documented learning towards productive methods of addressing a goal.

While the “delightful companions” themselves may seem like simple solutions, gaining a better understanding of how to create objects like these could have major implications for people diagnosed with chronic conditions such as diabetes, depression, obesity, hypertension, heart disease, and depression, and HIV. When long-term motivation is critical to the quality of life, social life, productivity, and life expectancy of people living with chronic conditions, design that supports them in an “everyday” capacity is fundamental to their success.

The Stamps Communications Team caught up with Sosa Tzec to learn more about his work, his approach, and the nature of design delight.

Q. Why is delight important?

Delight is a crucial element of human experience. When we experience high pleasure and arousal, that is delight. We connect with the present. Delight makes us feel that we are alive, and that our lives are good and make sense. Delight participates in the creation of memories. Those remarkable moments of high pleasure and arousal stay in our memories and heart, and become reflective instruments that help us make decisions — where we want to be, with whom with want to co-exist, how we want to intervene in the world we live in. Delight is so powerful that we end up having the urge of sharing with others how good we have felt. Delight works as a sociocultural adhesive within groups of people, including family, friends, and colleagues. Delight reminds us, in just an instant, that we are capable of living a good life.

Q. For a long time, form and function were driving forces in product design. In your view, why should delight be taken into account?

Regarding delight as the only, or major, driving force to bring something into existence would be a naïve claim. Delight is a relevant matter in design because of the positive impact it can foster for users. But it cannot drive the whole design process itself. To begin with, delight is not a “material” that designers add to their creations. Designers aim at designing for delight. They do their best to shape the features of a design to create remarkable moments of high pleasure and arousal. But they certainly cannot control how delight will unfold during the user experience.

Notwithstanding, delight does connect with a designer’s ability to find and create a successful balance between form and function. The key consideration here is to think of form-function as a composite. Dividing form and function is unproductive to comprehend how delight operates in relation to design. It is reasonable, but limiting, to regard delight as part of the form alone. It must not be forgotten that delight is a consequence of use as well, and that use relies on the structural, perceptual, and functional aspects of a design. Delight can derive from using a design efficiently and effectively.

From my perspective, delight (designing for delight) should be considered during the design process to guide judgment and action aimed at helping the user live a good life, not just to make the design flamboyant with the mere purpose of increasing profit. As I said before, delight is powerful; it shapes our identity and surroundings of our lives.

It is also important to keep in mind that form-function is not the only factor that drives a design process. Design also involves aspects of power, politics, beliefs, and tradition — and delight connects with all of them. Design is an act of judgment and volition, and as such, the notion of delight related to this practice is never neutral. Designing for delight is one way to promote, obstruct, and reframe the notion of living a good life by making the user associate the positive presence and productive use of a product with remarkable moments of high pleasure and arousal of the everyday life.

I want to illustrate this idea with a counter example. Have you ever come across a shower handle or a faucet, especially a “fancy” one, that you end up hating because you don’t know how to make it work? ‘How do I get hot water? Is it a turn to the right? The left? I don’t get it!’ Now, I would ask you, what about a shower handle or faucet that works just the way you need it to? What a difference! How delightful it is to have this as part of one’s life and not having to deal with those unusable ones!

Q. What are some ways that designers can measure the impact of delight? And why is it important to measure this?

As I said before, it is unproductive to think of delight as a “material” or “ingredient.” Designers cannot add a specific quantity of delight to make your design more delightful. It is impossible to prove that such a quantity will be recognized by all the users of the design in all the contexts of use and all user experiences. However, designers and design researchers count on different approaches to evaluating delight and its impact.

Some evaluations occur during the design process. Designers can use existing knowledge about human emotions — including the knowledge gained through their own life experiences — to shape the features of a design aimed at delighting the user. It is imperative that we do not underestimate or diminish this affective knowledge from the designers. They know about human emotions. They know what delight feels like. In addition, some researchers argue that a person learns and talks about pleasure by co-existing with other people, that pleasure is heavily influenced by what you learn about pleasure given your context. Designers must be empathetic and sensitive enough to grasp this social construction of pleasure, and later utilize their own subjectivity to envision those features intended to delight the users. I particularly advocate for this approach, because it acknowledges design as an activity distinct from science, in which the designer’s judgment and volition end up influencing the outcome of the process. Consequently, this approach urges the designer to be accountable for the persuasive effects of delight. Designers must think of and design for delight both ethically and thoughtfully.

Of course, the improvement of a design eventually requires the user’s input. Evaluations of delight involving users can be quantitative or qualitative. Influenced by the humanistic perspective of design that I follow, I focus on qualitative approaches in which the design becomes a probe to guide a conversation with the user. This conversation centers on how delight operates, especially in living a good life rather than validating the delightfulness of the design features. Certainly, there is value in evaluating the accuracy and effectiveness of the design features through a more traditional, not to say scientific, form of evaluation. My work does not focus on defining a measure of delight or of its elements. My work follows a humanistic orientation to design and delight, in which the qualitative data produced by having these conversations with users, and I would say among designers as well, about delight and the good life is more valuable for advancing the field of design while having larger implications outside of the design field.

Q. What is an example of delightful design that you admire? Something we may encounter in our everyday lives?

I think it is possible to identify how everyday design has the potential to provoke delight if we consciously pay attention to how their features engender engagement, surprise, liveliness, cuteness, serendipity, and reassurance. In this sense, there is always the chance of pointing out delightful design in our everyday life. However, a design feature that I remember well because of the delight it provoked in me is the Macbook breathing light (Fig. 1).

My first laptop was a white MacBook. I got it in 2004. I remember being captivated by the appearance and materials of my new computer. Setting MacOS up was a pleasurable experience as well! Nevertheless, one design feature that delighted me and bolstered my passion for design is the breathing light, which is one on the front of the laptop but covered by plastic, so it is not perceivable when the laptop is open. After closing the laptop, this light turns on. One can see the light coming through the plastic, and more fascinating, pulsating in such a way it simulates breathing. How crazy is that! I was in awe. I found it very useful to know when my computer was on and “taking a break.” This design feature engaged me, surprised me, it made the laptop look like a living being, it was cute, and it was convenient to know whether my laptop was on, giving me certainty of the current state of my computer and battery state.

Apple introduced variations of the breathing light until it was not necessary to indicate whether the laptop was sleeping, partially, as a result of increasing the duration of the batteries and making laptops slimmer. It was fun and useful while it lasted though! The breathing light taught me that design is in the details, especially, in those capable of making your heart pump!

Q. How are the elements of delight informed by cultural specificities? Is delight the same in the US as it is in India, for example?

Delight as an emotion is universal, but the delight produced by the features of a design is heavily situational. User-centered design comes with this notion of an archetypical user, which is certainly helpful for making design decisions. It removes the burden of thinking of all the specificities related to the people that will be involved in the context of use by addressing commonalities. Some commonalities apply to many contexts of use, independently of who the user is. Designers always turn to universal knowledge if that helps them produce a successful design. For example, the use of a certain wavelength of light that has been proven to arouse people, or the use of infantile features to encourage the user to develop an emotional bond with a design. Other commonalities are more local. I guess this is when we talk about specificities. These characteristics complete the definition of the archetypical user while they make her distinct. If designers are aware of how pleasure is built within the context of the archetypical user, it will be easier for them to comprehend how delight manifests in such a context.

In actuality, we’re all unique, with different physical and psychological capabilities, all of which are in constant flux as our lives unfold. As a result, design delight is situational: what was delightful to us as teenagers may not spark the same feelings as we age. Think of those super duper shoes that made you feel like the coolest person in the classroom. Even more, what was delightful now may not feel the same if we experience it later again. Have you seen those apps that get refreshed by swiping the screen down? Maybe the first time you encountered this design feature you felt delight. Probably, at this point, it is so familiar, that you do not care that much.

Remember, the designer can aim at delighting the user, but not add or remove the “element” of delight to the design. For this reason, my work explores a humanistic angle for delight, although it builds on what science and the humanities can tell us about engagement, surprise, liveliness, cuteness, serendipity, and reassurance as a launchpad for design. Designers can make use of this knowledge to inform the creation of their product, but they’ll also come to each project with their own judgement and volition. This means that you’ll see a true diversity in designer output: each designer will come with a different solution for the same design situation. And no matter how much universal knowledge the designer applies in her process, the intended delightfulness will be affected by the designer’s individual and unique understanding about delight, and the designer’s capability of understanding empathetically how pleasure is defined within the context of the user. So, in this case, “cultural specificities” are only one element in the broader definition of how design delight plays out.

Q. What are you curious to learn more about in this realm?

Design delight is a deep concept. I still have so much to learn, especially about the role of delight in living the good life. Defining design delight through six experiential qualities (engagement, surprise, liveliness, cuteness, serendipity, and reassurance) is just the initial step. At this point, I have more questions than answers. And that is right. It makes notice that design delight should be taken seriously. At this moment, design delight is presented as an approach to the production and analysis of delightful designs and experiences. However, my long-term goal is to produce a solid account built on research, a theory of how design delight supports living the good life.

To learn more about this project, read the M-Cubed project proposal.