A Career, Celebrated: Professor Janie Paul

In December 2016, Professor Janie Paul retired from the Stamps School of Art & Design, following over 20 years of dedicated service.

An Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, the University's highest honor for excellence in undergraduate teaching, Janie Paul influenced a generation of students and colleagues. In 2015, the College of Literature, Science and the Arts presented Paul with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

A highly respected artist, researcher, and author, Paul has written and lectured broadly about creating access to imaginative experience in marginalized communities with limited access to the arts. With courses such as Art Workshops in Prisons and Detroit Connections and her role as co-founder of the Prison Creative Arts Project (PCAP), she was an early advocate and pioneer within Stamps for utilizing art and design to connect across the boundaries of culture, class, race, and religion.

The following is an excerpt from Janie Paul’s forthcoming book, Worthy to the World. The book is a beautiful homage to the relationships formed with incarcerated artists during the PCAP project and annual exhibition.

I sit with Rafael DeJesus in the visiting room at Handlon Correctional Facility in Ionia, Michigan. I had written to him to say that I’m coming to interview him for my book, along with other artists here, arranged it all with the Special Activities Coordinator weeks in advance, but he was never told I was coming today. So when Rafael gets called to the visiting room, he doesn’t know who he’s going to see. He changes into his one set of street clothes, crosses the yard, and is seated in the row of chairs outside the visiting room. I am in the prison lobby, waiting to come through the gates. Even though the officer in the lobby called him out, the officers in charge of the visiting room don’t know why he’s there, so they send him back to his unit. I am still waiting in the lobby, half an hour, an hour. Finally someone realizes that Rafael is supposed to see me and they call him to come back from his housing unit. An hour and a half later, he crosses the yard again, and enters the visiting room. I come in and he recognizes me from the video that we send to the prisons each year.

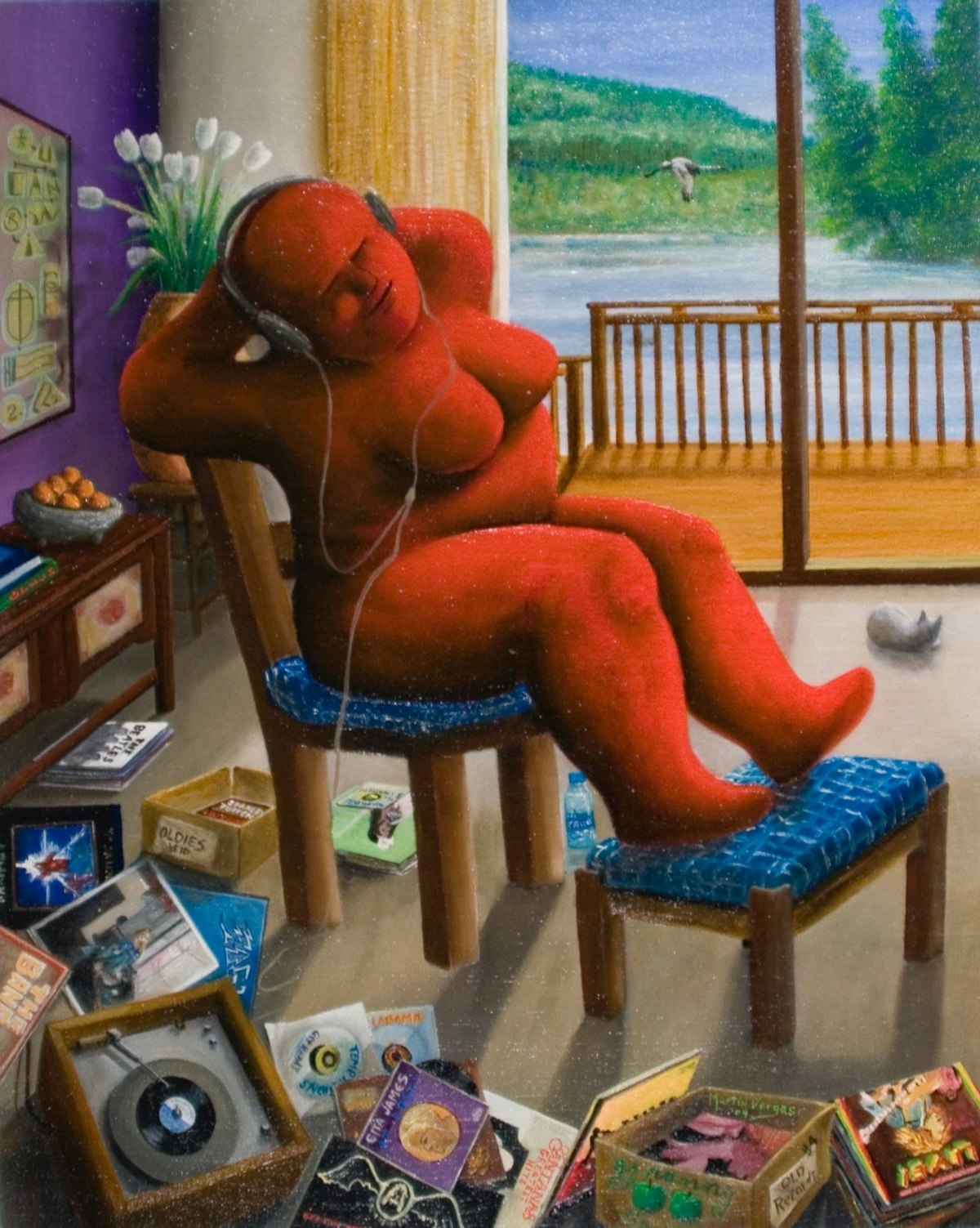

We had never met because he was at a facility where we weren’t allowed to meet the artists when we came to select art for the show. I was expecting an older man because I knew he had mentored several young men. But he is youthful and handsome, perhaps in his 40s. I bought a piece of his in 2007 and it hangs in our bedroom. It’s a picture of a girl on crutches holding a basketball, about to aim at a hoop outside the frame. Wearing a handkerchief on her head, a red shirt and a blue skirt, she’s in the country somewhere, a cabin, trees and mountains in the background, a road winding forward. He drew it in oil pastel, lots of reds and browns and very warm. I was moved by the poignancy, the rich colors and the way the figure was held and buoyed by the surrounding shapes forever in a gesture of anticipation.

A few years later, I was drawn to a landscape painting in the show and wanted to buy it, a covered bridge in the middle distance, mountains in the far distance, a road leading from the bridge and a man with a scythe walking near the bridge. Red bridge, dark luminous blue in the sky, very American rural. I am a sucker for those landscapes. I saw the signature – DeJesus. Yes, the richness and emotion in his work spoke to me and I became more curious about him.

The next time I heard his name was when I interviewed Dara Ket for this book, a young artist at West Shoreline Correctional Facility. He spoke of his two mentors, Rafael DeJesus and Alex St. John. There was love and respect in the way he spoke of them. As he spoke about his mentorship with DeJesus, I connected the generosity and strength Ket ascribed to him to the paintings I now owned. Sitting next to Rafael, he looked younger than I expected, but then from my vantage point at 66 almost everyone looks young to me. I notice the gray at his temples and realize he is older than I thought. I wince inside, seeing that he is on the cusp of middle age; knowing that he could grow old in here, knowing that it is more than likely, but so hoping that he doesn’t. For now, he is vital, high spirited and eager to talk, so we start to get acquainted. He moved to New York with his family from the Dominican Republic when he was fifteen, lived in the Bronx, often visiting his grandmother in Manhattan. I wonder if it was the same Dominican neighborhood that was two blocks from where I lived for twenty years on the Upper West Side, and yes, it was true. He had spent much time on the streets a few blocks from my apartment building. Excitedly we shared our knowledge of the Dominican restaurant on Amsterdam and other landmarks, realizing that we were both there at the same time in the 80’s. He said he thought I looked familiar. And now, here we are in a prison visiting room in Michigan.

Each winter for the past twenty-one years, I have been going to prisons in Michigan with a small group of other curators and volunteers to meet with incarcerated artists. We select their work for the Annual Exhibition of Art by Michigan Prisoners at the University of Michigan. Every year we go to about thirty prisons where we talk with over two hundred artists and select their work for the show. These visits are the heart of our project. We see old friends and discover new artists. We respond to their work and talk about it with them, making suggestions and giving validation in a place where it is scarce. Over the years I have admired their work and studied it, trying to figure out what makes so much of it so intense and so appealing. I have come to know many of the artists, particularly those who have exhibited for ten, fifteen or twenty years. I am in awe of them – of their resilience and ingenuity and in the ways they keep their spirits alive in the darkest of places. All this has deeply affected me, and my practice as a painter.

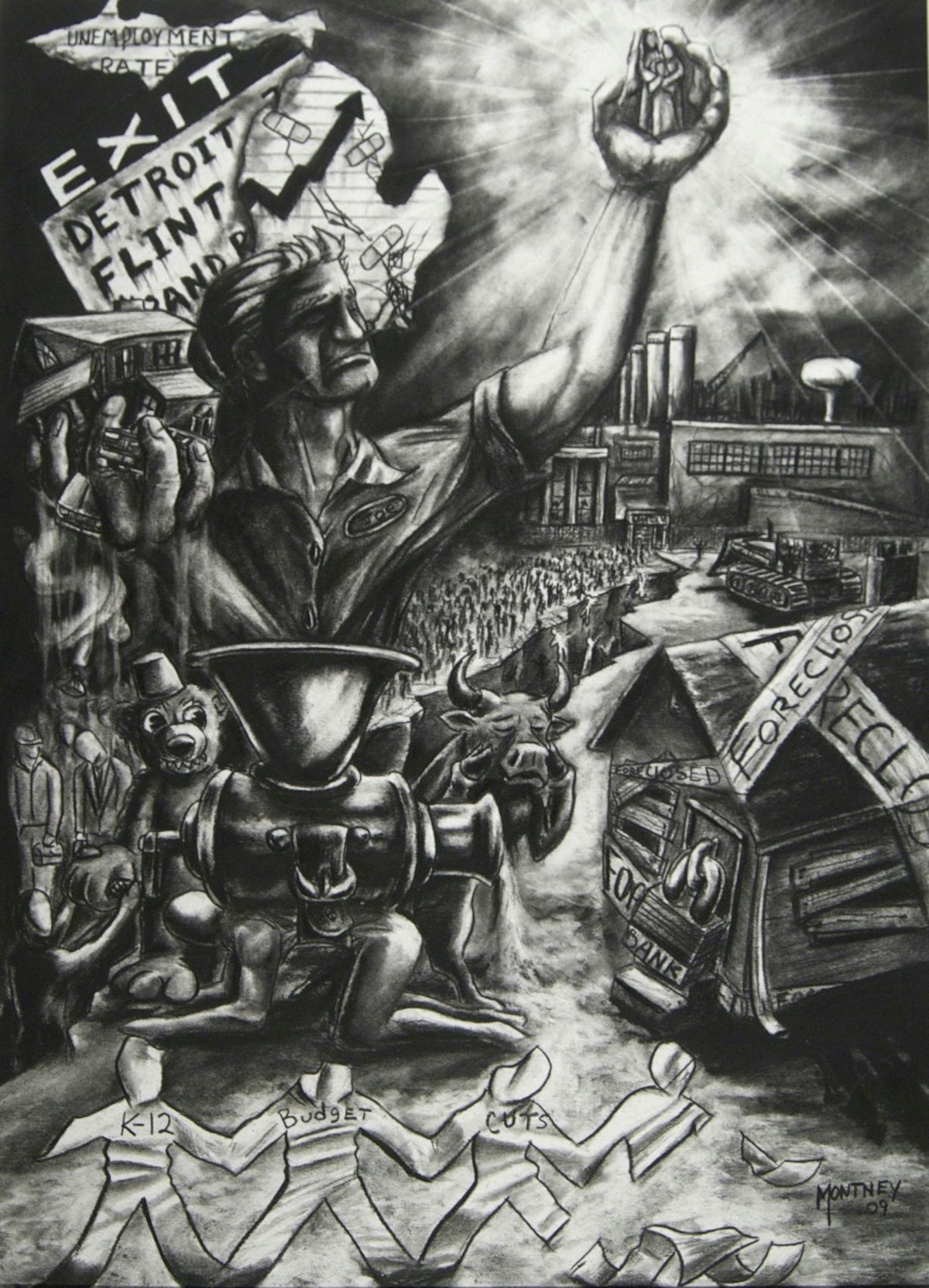

On my drive back from work at dusk I see the reflection of the trees in the Huron River and think of the many landscape paintings I have seen by prison artists, remembering their childhood in rural Michigan or imagining a place they have never been. Petting my cat, I think of the absence of touch and texture in their lives and the significance of pencil touching paper. In my studio, I have become more patient, more slow and more rooted in myself as I have come closer to these artists. In my studio, in a room I have designed and which feeds me in my work, I think of Rafael DeJesus who is serving sixty to one hundred years for a non- violent crime he did when he was young and the terrible and wonderful poignancy of his paintings; of Martin Vargas, who at sixty eight has been in prison since he was seventeen, has kept his spirit alive through art and has taught and inspired hundreds of artists throughout the system; of Duane Montney, a juvenile lifer who fights his sentence making powerful drawings about the sentencing of teenagers to life in prison.

In my studio I am surrounded by precious connections: museum postcards of a painting by Paul Klee, a self-portrait by Rembrandt, a Chinese landscape painting, books of paintings by Morandi and Bonnard, sketchbooks filled with notes and drawings. I put my mat on the floor and do yoga stretches; I look out the window and see snow falling on the oak tree and the empty nest in its branches. I sit in my dumpy recliner and contemplate the current drawing on the wall. And I know that my friends in prison are staying up late, sitting on a cold metal bunk bed with a drawing on their lap in near dark light, or sitting at the negotiated table space in the middle of an eight-person cube, or at a table in the recreation room, zoning out with headphones, fending off onlookers or enjoying the comments of artist friends and the admiration of corrections officers.

Inside artists become masters of gleaning inspiration and knowledge. Like me, they keep a scrapbook of images but their collections are cut out from a limited selection of magazines and newspapers. They memorize an image flashed on television for a few seconds or the texture of concrete, grass or leaves while they are in the yard to reproduce hours later from memory when they have time to work. They don’t waste time or resources. Art is their survival.

And so at the same time my own art has come to seem more urgent, more essential, more necessary and it has also become more necessary to tell the artists’s stories and to bring their work out into the world. It has become important to reflect on the whole experience of the past twenty one years – of this project that I started with my partner Buzz Alexander and its effect on so many people, and to reflect on art itself, because the urgency of the artists work has led me into the deep and essential questions we all grapple with: Who am I? How do I live? And how do I construct meaning? These questions are inter-related for incarcerated artists as they are for all of us and I return to them throughout this book as I consider the significance of making art in prison.

Imagine that you have just come to prison and have been put into a cell with another person or onto a bunk bed in a small eight person room for punishment – for five years, or twenty or forty. What will you do? First you have to get used to the routine of the day, the constant noise, the violent attacks and the threats of violence, the degrading treatment, the bad food. You feel angry and scared, possibly terrified. You miss all the connections to your life – your family, your clothes, your pets, your motorcycle or car. You start thinking about what you have done to get here, about people you might have hurt, property you might have damaged, or your innocence and how you were framed.

You are faced with time to reflect about your past and try to figure out how you will do your time. A prison artist I knew once told me that in prison you either grow or you die; there is no in between. Another man I knew told me that in his prison he thought that about 70% of the people had given up and about 30% were trying to forge a life and develop themselves. There are limited options, but definite possibilities for doing this. You can work out in the weight pit and play sports to keep your body in shape; you can practice your religion by yourself and by going to services, you can get books out of the library and read and in some cases order books on interlibrary loan; in the summer months, if your prison has gardens and you’ve been on good behavior you might get to have your own plot and then eat your own vegetables. You can sit down with a piece of state issued paper and a pencil and write, or draw.

Besides being faced with questions about how to spend your time, there is also the economic question of how to get money to buy necessary goods, stamps and envelopes. The food is terrible, so you want to buy what is available at the store. You may have a job but it pays only a few cents an hour. Or you may not have a job at all. You see that people are earning money or bartering for goods by creating greeting cards, decorated envelopes, portrait drawings of family members or tattooing. You might find someone to teach you how to do this, or you might figure it out on your own. You discover that you like the feeling you get when you’re drawing, the touch of the tool on the surface, and after you sell a few things, you have money to buy more materials. You buy a larger set of colored pencils and some card stock. You begin to spend more time doing this and less time gambling or fighting. And then you notice the really amazing art work that some of the experienced artists are making.