Ed West: So Called

For the past decade, Stamps professor Ed West has been engaged in a transnational research project on mixed-race identity. As a fine art photographer, much of Ed’s focus has been on the creation of a series of portraits of mixed/multi-ethnic people. But his research also led him to significant work in other areas of study, including history, sociology, critical race theory and anthropology. Here he talks about his project So Called, and the scope of the academic research that underpins it.

My work has always concerned itself with periods of transition or transformation, and my current work involves the imagining and imaging of the browning/creolization of the world’s population. It is said that to know something you must stand in its presence. And, in many ways, all of this study—whether in text or image—has been an attempt to stand in the presence of the histories and geographies of multi-ethnic people.

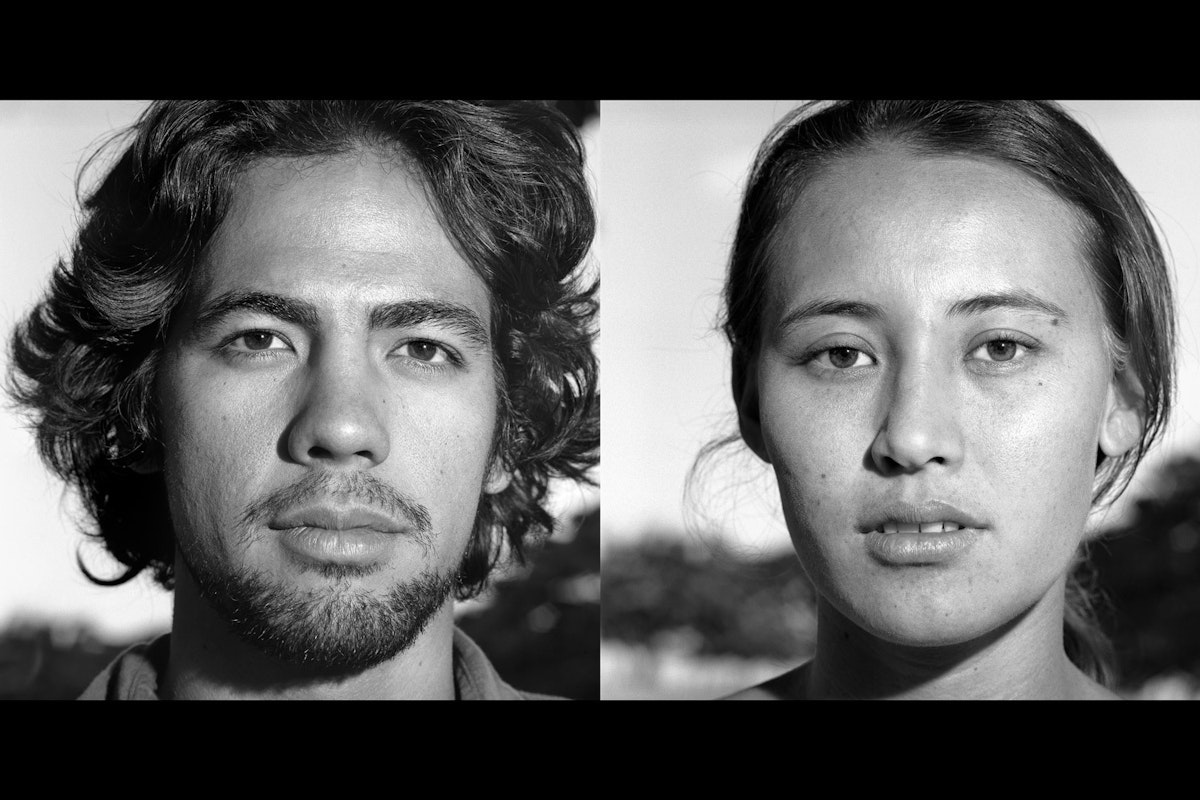

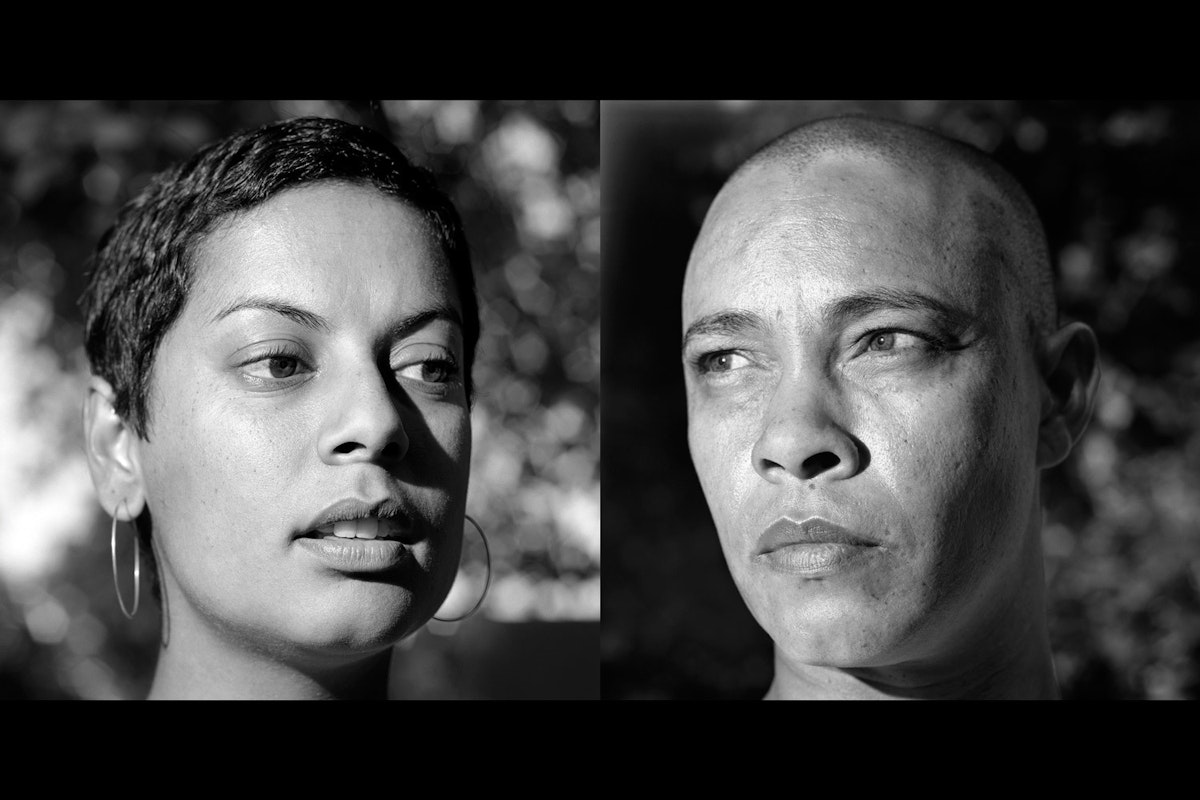

I’ve completed a series of portraits of the people who live in mixed race communities in Havana, Cuba; Cape Town, South Africa; and Honolulu, Hawaii. I chose these particular locations because I wanted “communities,” places where the majority of the population was multi ethnic. One of the charges that is frequently leveled against people of mixed race is that they are neither one thing nor another, neither this nor that. These portraits confirm that people of mixed race are this and that, and this and that across a global landscape.

The title of the project, So Called, also addresses how individuals and communities are defined. It refers to the liminal state that is mixedness, and alludes to both who names and how naming shapes communities and understandings of group identity. Which leads me to the other major, non-photographic, area of my work that centers on naming. Half blood, half breed, half caste, half and half, halfrican, hapa, hybrid—all names for people of mixed race. Naming is that moment of definition, when categories are solidified. The name given imposes its power on those named. As V.S. Naipaul observed “Twenty million Africans made the middle passage, and scarcely an African name remains in the New World.” This research involved the work of philosophers, historians, anthropologists, theorists, and political activists. The project’s name So Called highlights the contested place of naming in studying the mixing of races.

This is truly an advocacy project. To date the project has resulted in an exhibition and an artist’s book, and I’m hoping to use both to reach mixed race audiences around the country and around the world.

From a recent public presentation by Ed West on naming:

I believe that photographs have the power to displace us from our usual ways of seeing and provoke us into reflection and conversation about the meaning of race.

Clearly the mixing of the races globally occurred almost from the first moment that distinct populations came in contact with each other.

When one says mixed race in America and encounters the literature, one encounters the principle binary of black and white, and the power formation of dominance and subordination. Color is meant to be telling in the American story.

As black Americans, most of our ancestors came to these shores not as “Africans,” but as Ibo, Yoruba, Hausa, Kongo, Bambara, Mende, Mandinga, etc. And some of our ancestors—and this we cannot deny—came as Spanish, Portuguese, French, Dutch, Irish, English, Italian, etc. And more than a few of us... have some Asian and Native American roots.*

The history of the names that tell black americans who we are or where we come from has been largely erased.

The name given imposes its power on those named. Naming is that moment of definition, when categories are solidified. The people in these photographs aren’t named, their ethnicity isn’t named. I’ve intentionally not named them.

So Called is about the problematizing of that naming process. It’s a project not only about our history, but about who we will be moving forward.

* – Robin Kelley, “So, what are you?” ColorLines, September-October 1999