The 1983 School of Art Protests: How A Visual Community Fights Back

“Budget cuts to the arts, protests in the streets.”

While this could be a headline ripped from 2017, it also describes a moment in the Stamps School history when the university’s Budget Priorities Committee proposed to cut the school’s budget by 25%. It took the dogged determination of a dean, the disciplined vision of a faculty member, and the mobilization of over 300 art and design students to safeguard the school from what would’ve been a devastating blow.

Setting the scene.

In 1974 — after a long history of art and design education developing in a variety of units on the U-M campus — U-M approved the recommendation that art and design education separate from the College of Architecture and Urban Planning to form the newly minted School of Art. The school moved to north campus, into a brand new facility, with a brand new dean: George Bayliss.

“We moved into a new building and we had five retirement positions to fill at the same time,” reflects Bayliss. “It was just really like dying and going to heaven for us.”

One of those new hires was Allen Samuels, now a Professor Emeritus and Dean Emeritus (he served the school as Dean from 1993-1999). “People were young and enthusiastic and you could really feel it,” Samuels said. “The paint was fresh and everything was brand new.”

A storm approaches.

As sunny as things were at the School of Art, the national economy was plunging into a deep recession by the early 1980s. The state of Michigan, with an economy so directly linked to the declining automotive industry, responded to the recession with a reduction to higher education allocations. With public universities in the state receiving drastically lower contributions, administrators at the University of Michigan found themselves looking for cost savings and cuts on campus with the development of a 5-year, $20 million plan for retrenchment and reallocation.

In the spring of 1982, Dean Bayliss was working in his home studio when he received a call from a U-M provost. According to Bayliss, the provost relayed the fact that President Harold Shapiro and the University regents had convened and decided to conduct a review of three schools at the University: the School of Natural Resources, the School of Education, and the School of Art.

Dean Bayliss understood the need to economize, but could not fathom the instinct to target three specific schools. “That’s what really kind of enraged all of us — the fact that we were selected out of a crowd,” Bayliss said.

Speculating on why the School of Art was targeted, Bayliss said, “The provost seemed to have this question in his mind all the time: ‘when was the art school going to join the university’s intellectual dialogue?’ My answer to that: intellectual dialogue is visual as well as verbal. I don’t think he understood that.”

The gauntlet is thrown.

During the 1983 academic year, a subcommittee reviewed the School of Art. Despite the subcommittee’s review specifying that the school could only realistically absorb a 10-15% cut, in March 1983 the University’s Budget Priorities Committee proposed a 25% cut to the School of Art. While a 15% cut would mean the inability to replace retiring faculty and gutting several fields of study from the curriculum, a 25% would be a massive blow resulting in a 40% reduction of faculty, a significant reduction in undergraduate enrollment, and an insurmountable hurdle to resourcing students with the facilities needed to create strong work.

Worst of all, as devastating as the cuts would be to the learning community at the School of Art, they did little to address the larger needs of the university budget. “It was completely insignificant in terms of the amount of money it would actually save,” said Bayliss.

As president of the National Association of Schools of Art, Bayliss was also deeply worried about the national precedent that the cut could set. “I would go to meetings of the association and people were very anxious to know about what was going on. Many felt that if art at Michigan could be attacked by an enlightened university administration then they in their own schools would very likely be subject to similar attacks.”

Hope was not lost, though. In a Michigan Daily article published on March 4, 1983 Bayliss is quoted: “This (recommendation) is not final. I have a hunch we can get support if we just go out and get it…We must enlist the support and awareness of others who don’t realize it yet.”

Bayliss sought the help of Professor Ted Ramsay. A popular professor of painting, Ramsay was interested in asserting the criticality of creative practitioners through disciplined, organized means. “George asked me if I would be willing to work with the students and see if we could come up with some kind of a solution that wasn’t radical,” Ramsay said. “I thought to myself, ‘you know, we are a visual school. How can we be visual and state our concern without creating chaos?’”

In a loud world, silence gets noticed.

As a child growing up in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, during World War II, Ted Ramsay was deeply influenced by the coordinated community response to the war effort. “The bands were patriotic, the radio programs were patriotic, and a lot of the young men from church went off to war,” Ramsay said. As a student at the University of Iowa, Ramsay participated in ROTC Officer’s Training. These two elements of personal history, combined with his experiences with the “loud, frightening” protests of the 1960s, informed his philosophy and approach to addressing the proposed budget cuts. “My feeling was, after thinking about this for a few days and making notes, that we needed to have a silent protest.”

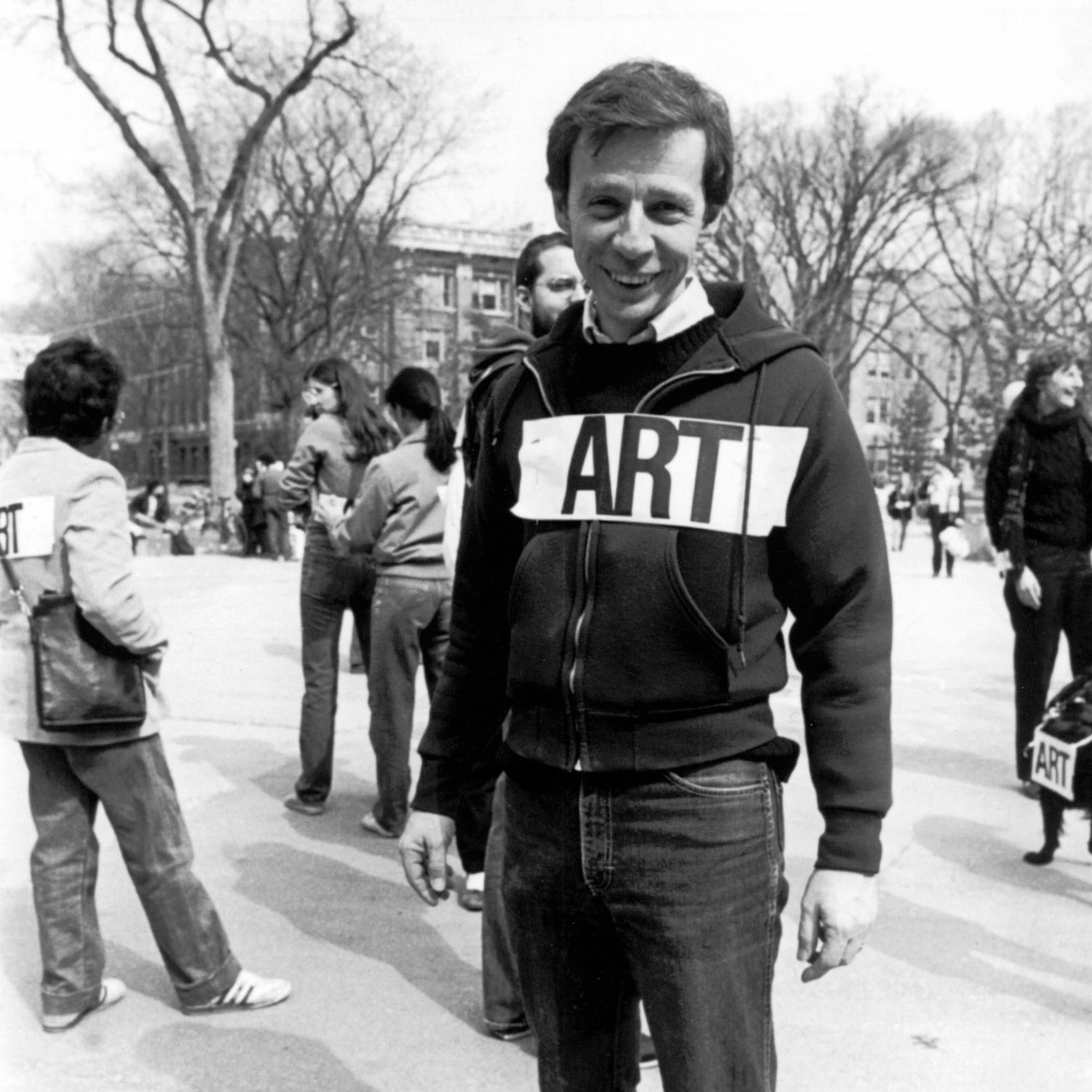

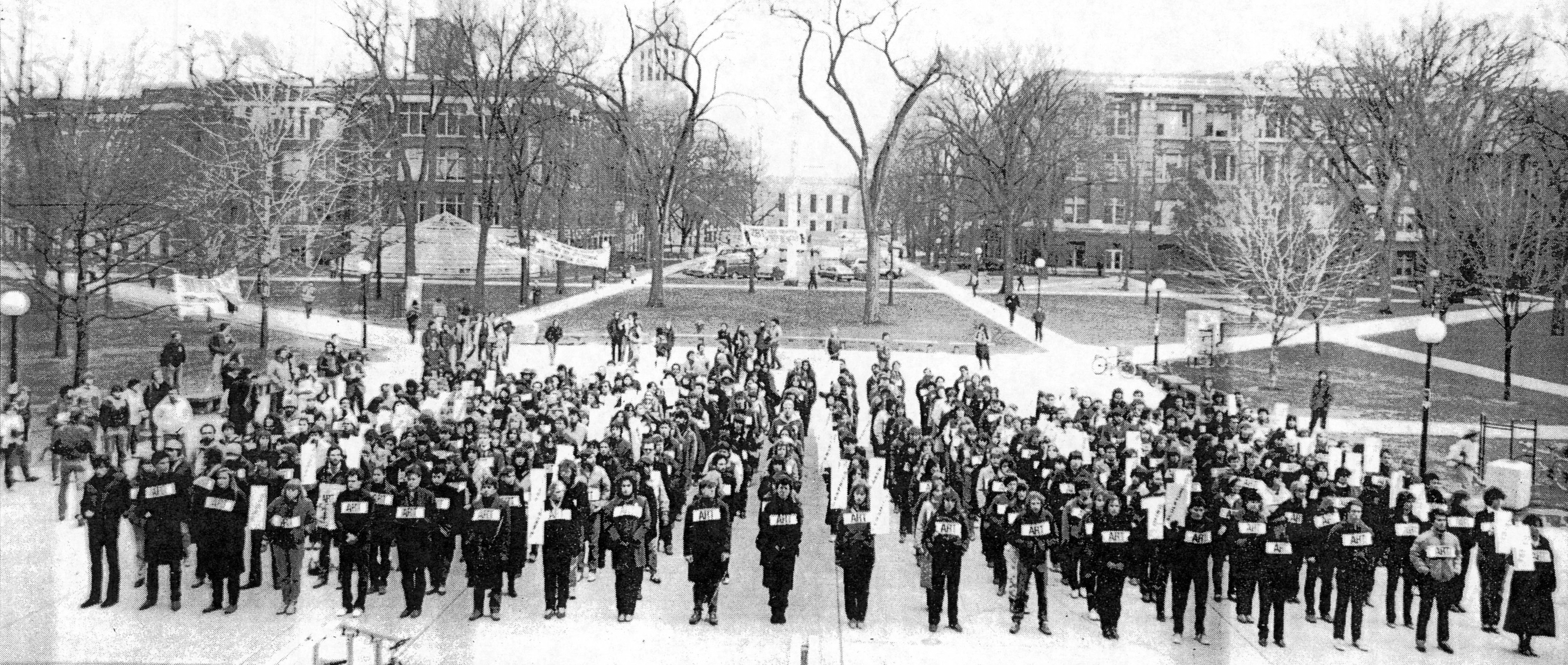

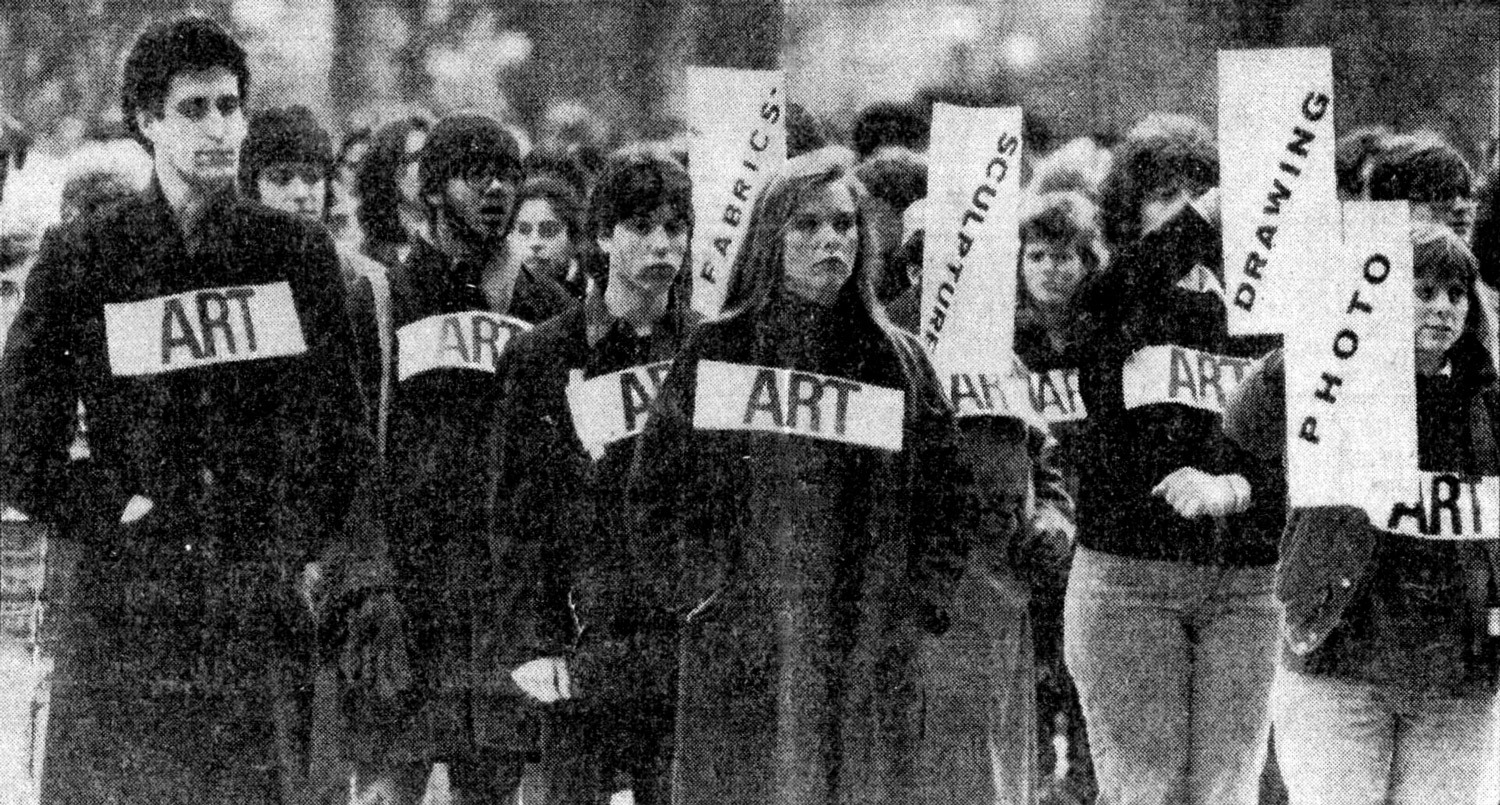

With boots-on-the-ground support from professors Mignonette Cheng and Bill Lewis and from campus police, Ramsay coordinated a series of highly visual protests unlike any other seen on the University of Michigan campus before or since. During the week of March 7, 1984, over 300 School of Art students convened for the first in a series of protests. Dressed uniformly in black with the word “ART” pinned to their chests, the students marched in silent, highly choreographed military fashion to the Diag. Standing “at ease,” and an arms-length away from one another, the students attracted crowds of spectators, all eager to see what would happen next.

“Before the first protest, I told the students about Geronimo,” said Ramsay. “When the military troops were coming in the canyons of the southwest, Geronimo defended his area by sending warriors to the tops of the canyons to yell and clap, creating the sound of a huge presence. It unnerved the troops quite a bit.” The School of Art students adopted this tactic, creating waves of clapping in unison. While the clapping was light, the approach in unison demonstrated thunderous solidarity.

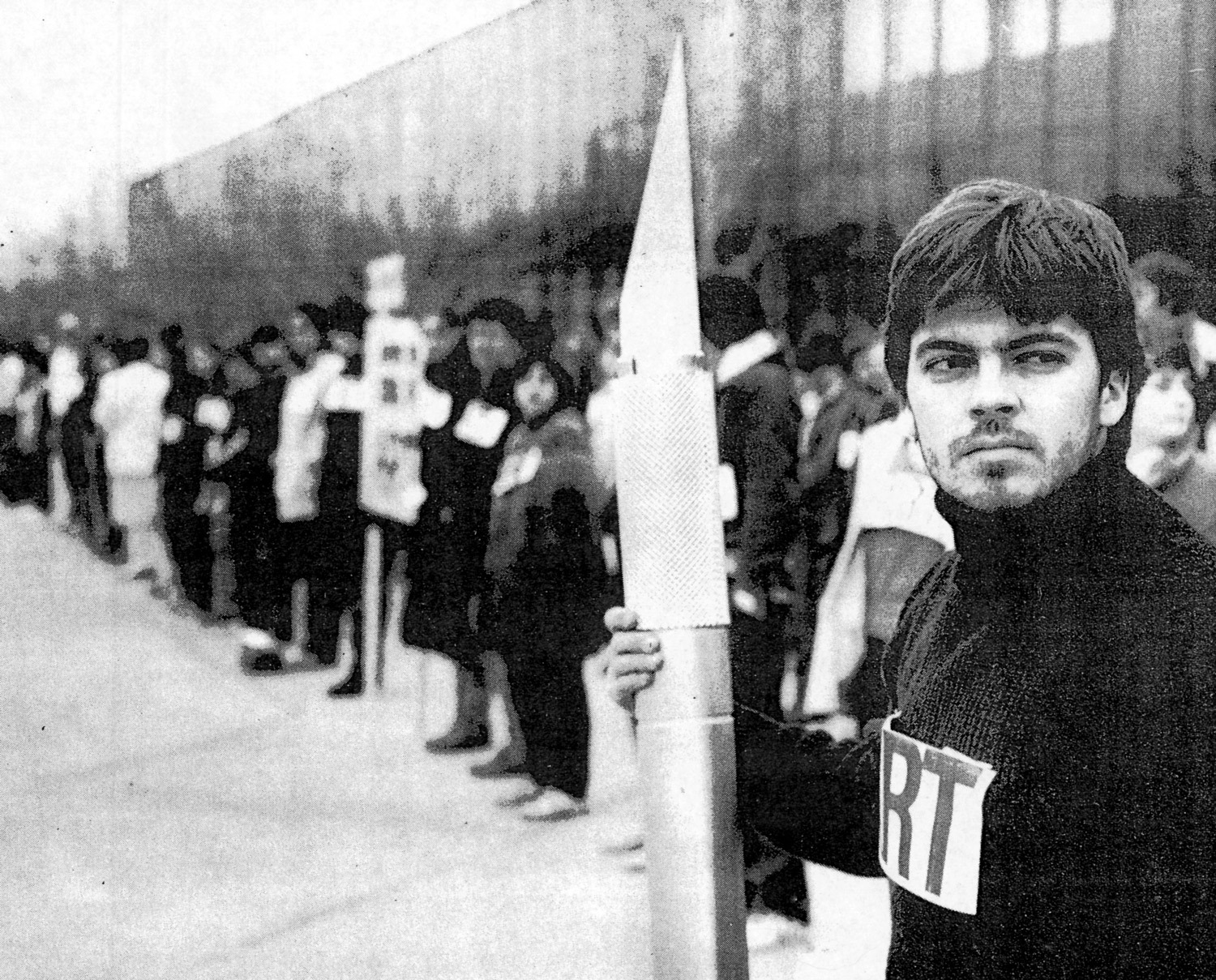

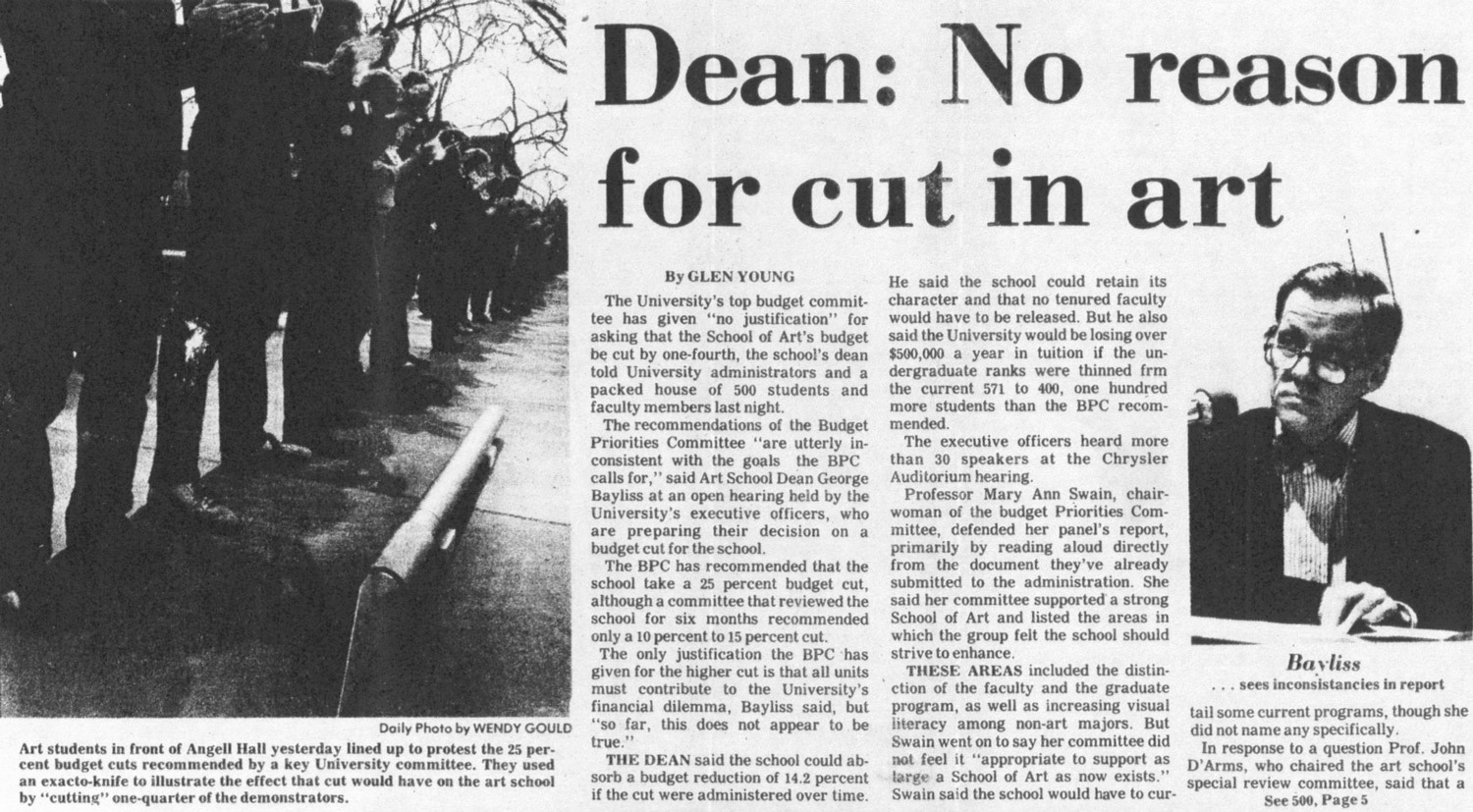

When the students protested on Wednesday, March 9, students in the design department created a six-foot tall X-Acto knife from plumbing pipe. Still moving in military fashion dressed uniformly in black with “ART” pinned to their chests, the students silently marched from the Diag, to Regents Plaza, and ended at the U-M Museum of Art (UMMA).

“The police stopped traffic as 400 students marched across State Street,” Ramsay recalls. “At Regents Plaza, we assembled in formation before this sweet woman from the design department walks up to the first four rows with the X-Acto knife. She goes like this” — Ramsay mimes the woman tapping a classmate with the X-Acto — “and 25% of the students gathered go down on their knees in front of the administration building.”

The March 9 silent protest ended at UMMA, where the X-Acto knife “cuts” were performed again, but this time the demonstration ended with the unfurling of a banner from the face of the museum, declaring: SUPPORT THE SCHOOL OF ART.

At its core, the silent protests demonstrated deep discipline, dignity, and commitment to letting powerful imagery speak for itself. “Our visual statement was on news reports before Twitter and cell phones and everything,” said Ramsay. “If we’d had that we would’ve stormed the place, no question about it.”

Behind the scenes, a School of Art senior named Amy Peck (now Amy Peck Abraham) was running PR for the protests to secure coverage.

“I was inside of the School of Art’s main office, on the phone to the radio station, to the Michigan Daily, to the Detroit Free Press talking about the protest,” said Peck Abraham, who was involved in both political science studies at LSA and jewelry making at the School of Art. “It was the best place for me to help — I was comfortable doing it, and I couldn’t be in two places at once.”

Ted Ramsay reiterated the importance of PR to the silent protests. “Students sent press clippings home and soon you had alumni from all over the United States calling the president asking what was going on. I think that made a big difference.”

The verbal attack.

On Monday, March 15 the Review Committee hosted a public hearing in the Chrysler Center Auditorium on North Campus to allow the School of Art to oppose the cuts. Many individuals represented the School of Art that day, including Dean George Bayliss, current students, alumni, and professor Allen Samuels. News accounts of the hearing document School of Art criticisms surrounding the accuracy and reliability of the projected savings. The rationale for the School of Art being targeted for review was also the subject of deep scrutiny.

Allen Samuels recalls his testimonial: “I asked, ‘What is the reason for us being targeted? For us being on your list?’ They gave us only two minutes each to speak before ringing a bell to signify we should stop. My bell rang and I just didn’t stop. I didn’t stop.” Samuels reiterates, “They never did provide their criteria for targeting our school.”

“I’d been spending my summers working with people doing education policy in Washington DC,” said Peck Abraham. “I was equally involved in my political science studies as my art studies. So when it came time to testify, I thought ‘I can write that. I can get up in front of a bunch of folks that are older than me and have more power than I do and tell them what I think.”

While cuts were made to the school in April 1983, they were far less than the proposed 25%. “Ultimately, we were saved,” said Samuels. “I’m proud of my part in this. Years later, when I served as dean, I made a point of clarifying every chance I got how our school and all things visual are central to being human and central to the mission of a world-class university. Take from our world every designed image, designed object and designed space and what do you have?

Culture, humanities under siege in 2017.

In 2017, the Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design at the University of Michigan has benefited from funding from central U-M administrators as well as private donors. However, funding to national public arts and culture programming is under siege. Many are hitting the streets with visual communication campaigns of their own — pink hats, handmade posters, and the undeniable narrative crafted through sheer volume, frequency, and pervasiveness of their protests.

“When we get philistines in the government the first thing they want to do is cut the arts and humanities,” said Bayliss. “And the amount of money that would be saved is infinitesimally small. For example, in the federal government they spend 4 trillion dollars a year. Cutting out the arts and humanities endowments they would save something less than $500 million. This is less than a tenth of one percent of the budget. So it’s not really a financial matter, it’s a philosophical matter.”

As artists and designers, the Stamps community is in a unique position to take a stand. As Professor Emeritus Ted Ramsay states, “We are visual people. We have the ability to make a visual statement that people will never forget.”