Being Well and Staying Well: Stamps Design Charrette Focus on Geriatric Care

Holding up a brightly colored plastic pill box, Grace Jenq called out its flawed design as she addressed a recent charrette hosted by the Stamps School of Art & Design focused on better serving geriatric populations.

Jenq is associate professor of geriatrics at Michigan Medicine. She was sharing several slides of statistics on older Americans and the problems they face, when she noted how the simple, ubiquitous box had been divided by days of the week but didn't account for the medicine many seniors have to take multiple times a day or the reality that many seniors don’t have the dexterity needed to open these pill boxes.

"This design just doesn’t work," she said.

Funded with a grant from the nonprofit, seed-funding organization VentureWell and the Lemelson Foundation, the Hacking Health Design Charrette was organized by Stamps professor Stephanie Tharp and Ross School of Business lecturer Eric Svaan. The pair envisioned the charrette as a way to give students in their Integrated Product Development (IPD) course for Winter 2018 a head start on the human-centered research required to produce the next generation of products for senior citizens.

The daylong workshop was held at the MDes studio on November 10, 2017 and included about 40 participants, including Stamps students and faculty, school of engineering students, health care and wellness professionals, and local senior citizens.

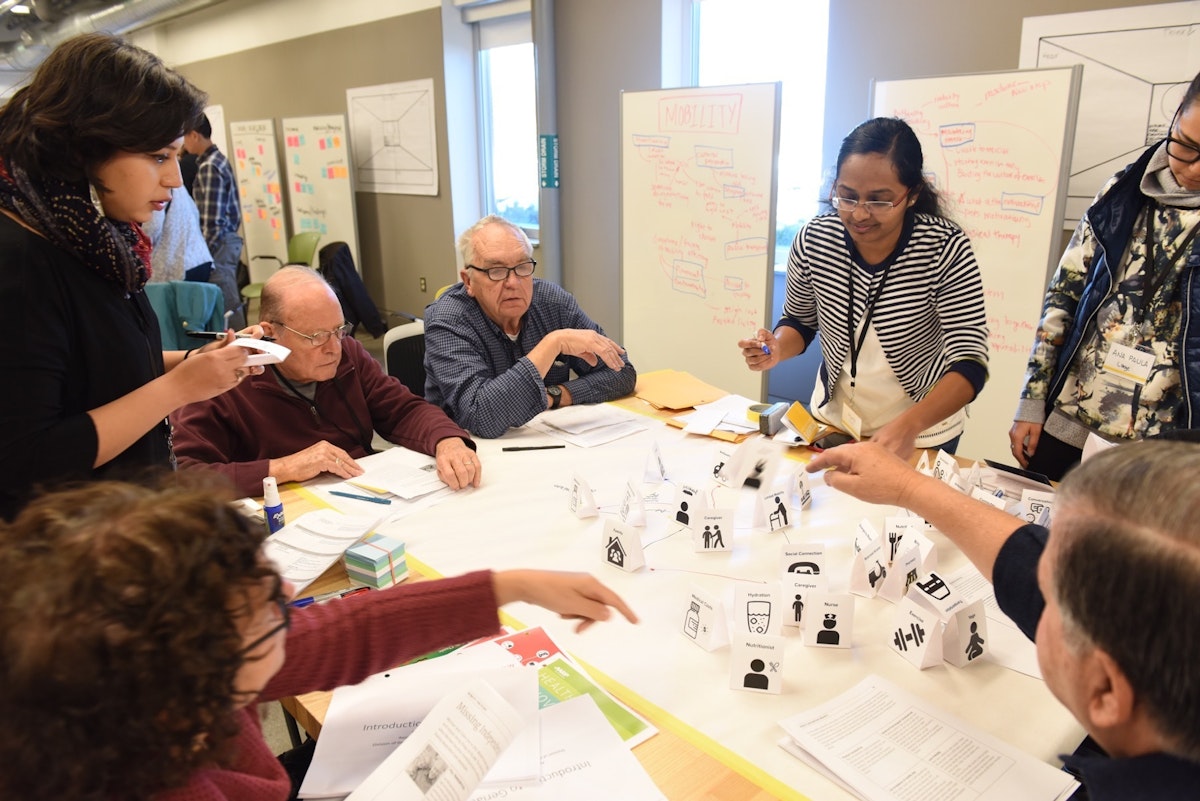

Working in groups of eight, participants explored issues related to the topics of Aging With Vitality, Social Engagement, Mobility, Diet and Nutrition, and Remote Access to Healthcare.

The charrette also gave first-year students from the MDes Masters of Integrative Design program a chance to facilitate a participatory design process, according to MDes faculty advisor Hannah Smotrich. "To manage participants, engage people, and feel the rhythm of the group, that's very much part of the skillset they're trying to learn," Smotrich said.

Acting as facilitators, first year MDes students — with support from the second year MDes cohort — led participants through a series of exercises meant to help them gain context, develop empathy, and produce problem statements around their respective issues.

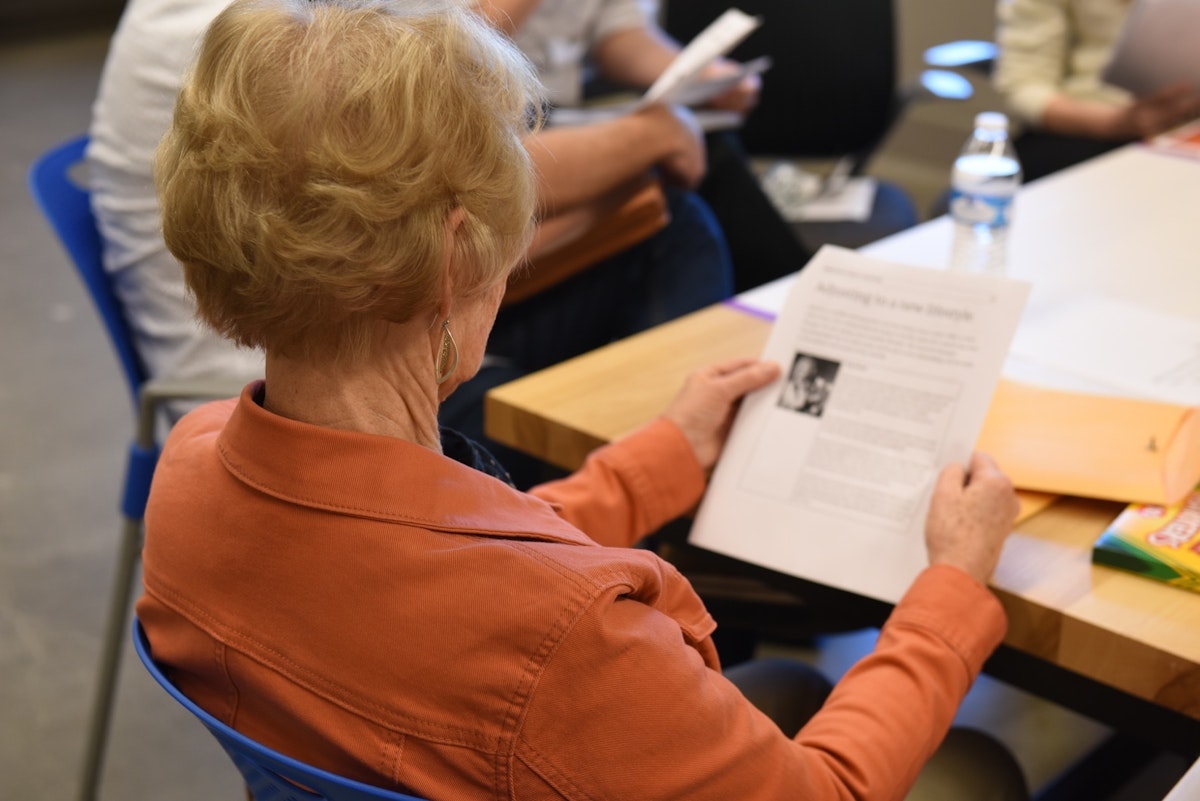

To accomplish this, each group began with a short case study about an older individual to help prompt members' thinking about what life might be like for them. There was Sonia, the wildlife photographer being told to consider retirement; Elaine, the grandmother who didn't have anyone to play cards with anymore; and recent divorcee Steve, who was having trouble eating since splitting up with his wife.

Reactions to the Sonia prompt were divided at first in the Aging with Vitality group. Some members agreed with her physical therapist: she should think about slowing her active lifestyle after a minor, but nagging, knee injury in her early '60s. But local senior and nurse Nancy Prince strongly disagreed. "They peg you into a group when they look at your age," she said, citing her own experience with primary care doctors.

"They're like, 'You're 74. What did you expect?' she said. "I'm here to be well and stay well. I don't want to hear, 'You're doing great for your age.' That's why I really reacted to that."

From these initial briefings and responses, groups filled in the gaps to flesh out their characters' lives and worlds with wants, needs, hobbies, and social networks through various mapping activities.

For experience mapping, participants represented people and things in their characters' worlds by placing pop-up, card-stock avatars printed with icons for "family," "medicine," "transportation," "surgery," "loneliness," and many more on a large, white sheet of paper. Then they drew arrows to show the connections — and disconnections — between them all.

At the Social Engagement table, participants wondered out loud how easily 82-year-old Elaine could learn new technology and navigate social media platforms, like Facebook.

"A smart phone changed my mother's life," said Ann Verhey-Henke, managing director of innovation and social entrepreneurship for the U-M School of Public Health.

"My grandmother loves emojis," chimed in second-year MDes student Brandon Keelan.

Senior participant Ruth Mieras confirmed: her main connection to her grandchildren is through texting. She demonstrated her one-key-at-a-time technique with her index finger (I haven't gotten this, yet," she said, acting like she was typing with two thumbs) and shared that she even texts as a way to talk to her husband while he watches TV, because he wears earphones when he does.

Informed by their morning mapping exercises, groups worked in the afternoon to write problem statements built around their characters' values, needs, and barriers to those needs.

These statements are one of the main deliverables from the event that will be handed over in January to students taking the IPD course, Tharp said. Students will also have access to the primary and secondary research leading up to the event, and other documentation of the day itself. Those students will then continue with researching, designing, and producing products to address these problems.

Over the semester, students will compete in teams of undergraduate and graduate students from Stamps, and graduate students from Michigan Engineering, Ross School of Business, and the School of Information. Each team will develop a product and bring it to the "marketplace" in an online and physical tradeshow in April 2018.

Svaan said the follow-up course is prepared for a better start than previous iterations of the IPD class he and Tharp have taught thanks to the design charrette.

"We have this rich, primary knowledge base that was generated in the conversations today that included people in the target demographic the design challenge is going to be aimed toward," he said.

Medical graduate Julie Zard didn't expect the charrette to be as participatory — or fun — as it was. Zard is from Lebanon and seeking a medical residency in the US. She appreciated the creative, collaborative approach designers bring to wellness issues.

"I just like the atmosphere, because it's very engaging," she said. "Everyone is encouraged to participate in a way that no one feels embarrassed or like their idea is not going to be very interesting."

At the end of the day, each group reported back to the larger one on the work they had done as well as some parting thoughts. Zard and her group — Remote Access to Health Care — turned up what seemed to be one of the bigger overall takeaways of the event: "The problem might not be what we — as younger designers — thought it was."

But they didn't start there. Facilitator Katherine Jones (MDes, '19) explained that the group's prompt included a woman who wanted to talk with her doctor more often. The obvious answer at first was, "they need internet" or "they need videoconferencing."

"Through the different exercises, my group was starting to understand that maybe actually it's that they want social engagement," Jones said. "They want connection. Maybe the doctor is the only way they think they can get that. So it was really fun to watch them start thinking, 'I know what the solution is,' and then go back out and come back and around be like, 'Oh, wait a minute. Maybe it's actually this.'"

Stamps seniors Rachel Krasnick and Madeline Helland (Stamps '18) have both taken the IPD course and are working as teaching assistants during the Fall 2017 course. For Krasnick, first-hand input from senior participants made the experience more valuable.

"A lot of the time when we're in class, we're thinking about the user, but we don't have access to talk to them, so it doesn't let us empathize as much or connect with the problem," she said. "Here it was great, because we had the people here with us to hear their opinions about things."

Before group work started, Stamps professor emeritus and dean emeritus Allen Samuels shared some thoughts on his 50-years of product design work, specifically for underserved populations of the poor, disaster-struck, and elderly. He cautioned participants to steer away from stereotypes and generalizations and to listen to individuals tell their stories of "this is what Parkinson's means to me" and "this is what getting out of a chair is like for me."

"We're not really talking about patients," he said. "We're talking about people."

When thinking about aging, Samuels reminded that everyone will reach a point when they are at their best in life at something, but at some point, we can no longer do what we used to. "This reality doesn't have to be demoralizing or depressing."

As the day came to a close, Ann Verhey-Henke offered a similar sentiment as she reflected on her group's work. For one of their exercises, group members had identified potential "pains" and "gains" for their character, Elaine, as she moved into a new phase of her life, and Verhey-Henke noted the gains had won out 2 to 1. "We would like to challenge you to design a solution that focuses on the gains," she said to the designers in the room.

In closing, she noted that aging well seems to come down to finding a balance between dependence and dignity. "They tend to be thought of as mutually exclusive," she said. "But we don't think they have to be."

Story by Eric Gallippo. Images by Stephanie Brown.