Jon Verney (MFA ‘16): Thermophile - A Collaboration with Nature

“It was like painting with the earth.” Stamps MFA candidate Jon Verney welcomes the uncertainty and imperfections that come from a collaboration with nature in Thermophile, his MFA thesis project.

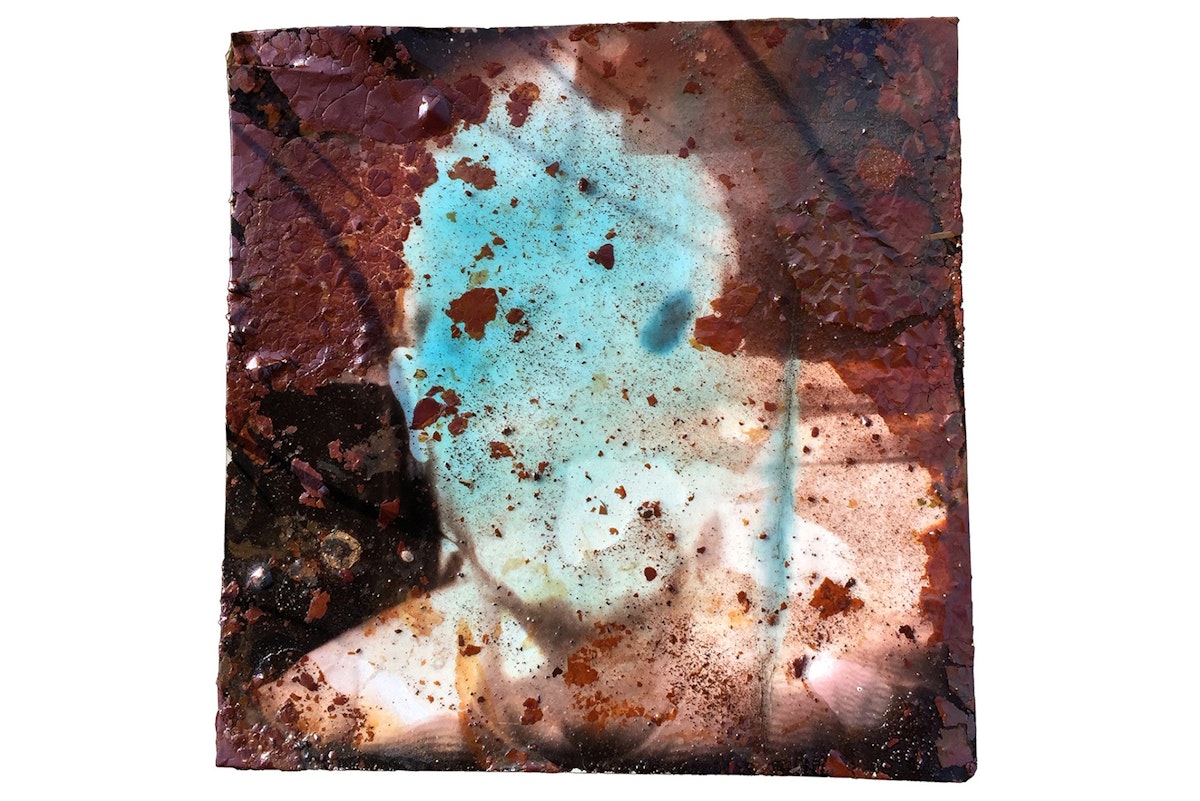

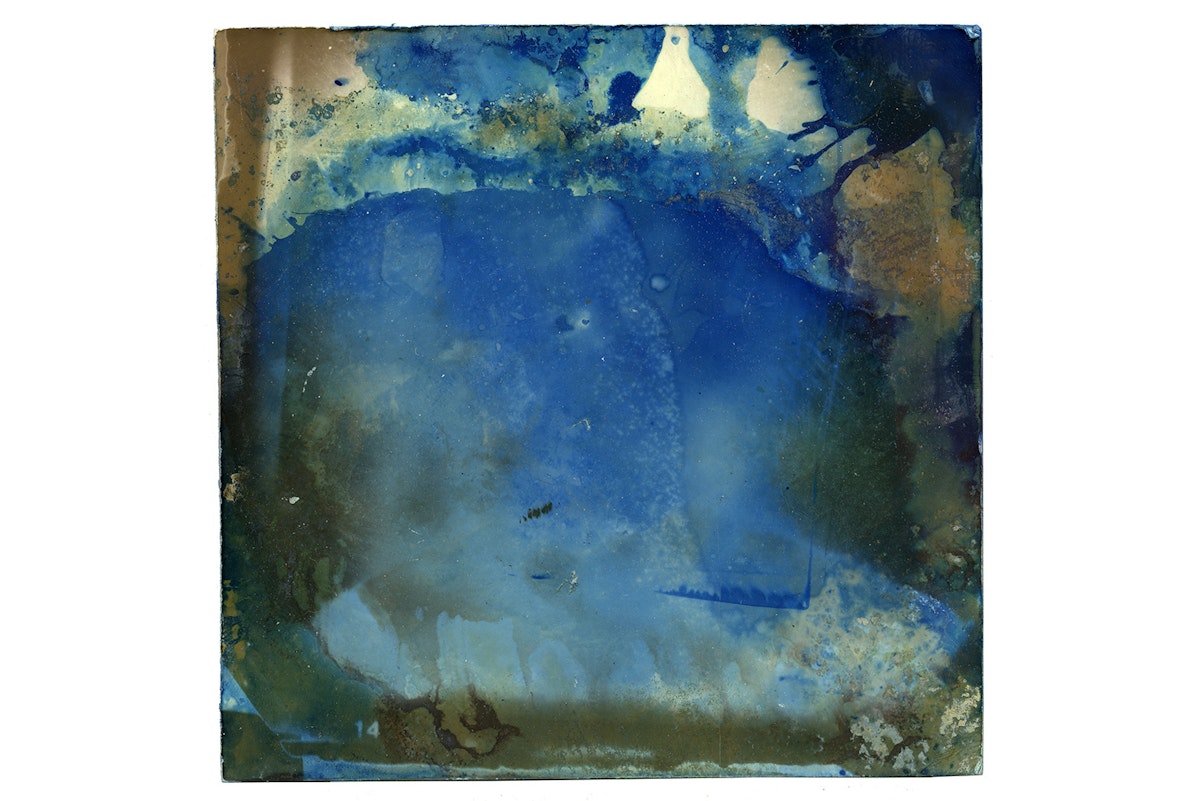

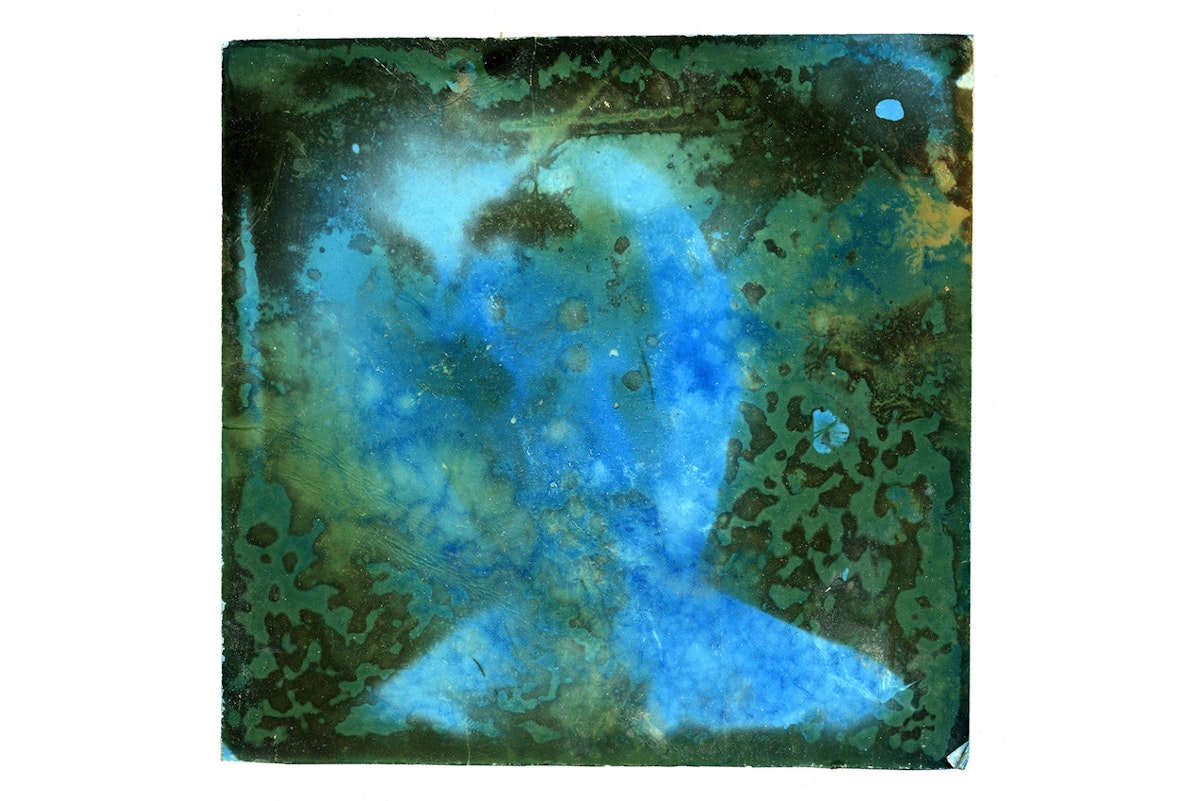

Traveling to geothermal hotspots in Iceland, Wyoming, and California's Salton Sea, Verney used the water and mud in hot springs, geysers and mud pots to redevelop silver-based photographs. The process resulted in images with a wide variety of colors and textures, as unique as the landscapes they emerged from.

Verney sat down to discuss his work in advance of his MFA Thesis exhibition, opening March 11th at the Argus II building in Ann Arbor.

How did you come up with the idea for Thermophile?

I've always been fascinated by the alchemy of film. Since my introduction to the medium I've been obsessed with dissecting it – to get at the guts of the stuff, to find out what it's made of and how it works.

The genesis of this project came to me years ago when I was working as a darkroom technician at a school in Italy called SACI. Part of my job was to mix the chemistry for the black and white photography classes, including solutions for sepia toning.

Technically, sepia toning is known as “redevelopment toning”. Its a two-step process. First, a finished black and white image is placed in a bleaching agent, which erases the image and reverts the silver in the emulsion back into an undeveloped state. Then, it's placed in a bath of sodium sulfide – essentially, a sulfur bath. The sulfur latches onto the silver and forms silver sulfide, a new chemical compound that causes the image to redevelop in warm brown tones.

The professor I worked for there, Romeo DiLoreto, is a master of photographic chemistry. Once, after we made a big batch of sepia toner, he mused that the high concentration of sulphur in a thermal spring could cause a bleached photo to “naturally” sepia tone. This seemed totally bizarre to me, so I tried it.

I had a photograph I had taken of my late grandmother's hands opening a letter. I placed it in the bleach and watched it fade away, then I took it to a hot spring south of Siena – the first hot spring I had ever been to. Immediately after laying the image in the mineral-rich water it began to change. The paper turned orange, then crimson, and then the image completely reappeared in a warm, bronze sienna.

Standing there with all this hot water gushing upwards from deep within the earth and watching this obliterated image become reborn by the landscape was a truly extraordinary, almost baptismal experience.

So after this experiment in Italy years ago, was this something that you kept in the back of your mind, or actively pursued?

It remained in my mind, but it took me years to come back to it. When I was presented with the opportunity to go anywhere in the world to conduct a project while at Stamps, I wanted to challenge myself to make a series of work that would actively be informed by the place I was heading. I had this strong intuitive drive to go to Iceland, which got me thinking about a project that would allow me to interact with its many hot springs.

I decided to create a large series of identically-sized photographs that I would bleach and transport, en masse, to Iceland, going on a sort of pilgrimage to as many different thermal sites as I could throughout the island.

The unexpected results from this project led me to continue to explore geothermal landscapes for my thesis. A few months later I took another set of photos to Yellowstone National Park, in Wyoming – one of the largest thermally active landscapes in the world. However, the Park Service is pretty leery about people interacting with the thermal features there, so I had to suss out springs around the periphery of the park to work with.

Later, I traveled to the southern shore of the Salton Sea, a large, man-made sea above the San Andreas and Imperial fault lines in California. There I worked in these sprawling, roiling, thermal fields that are rich in iron and sodium, which created a thick mineral crust of salt, sinter, and sulfur.

Why did you choose to work with self portraits in this project?

Initially I was thinking about my “baptismal” experience in Italy, and thinking of baptism in the secular terms of it being a kind of punctuation mark in something's existence: “from here on out, you're going to be different.” The fact that one of my photos enters a pool one way and comes out changed… I find that quite powerful.

I wanted to make something that dealt with the corporality of the body. During the thermal toning process, my photographs are immersed in hostile environments – superheated acidic waters, volcanic steam, and boiling mud. I felt like the only body I have the authority to virtually subject to that process a thousand times would be my own. An image of my face is an image I completely own and can account for.

I also wanted an image that would act as a sort of vehicle for the chemical reactions. My face grew less important over time, as the project grew into being a sort of collaboration with the earth.

Working in three different locations that are thousands of miles apart, it felt like I was shaking hands with a vast and unknowable geological force, and allowing it to speak through these tiny pieces of paper.

Did you run into any unexpected results in the process?

Well, I had first hypothesized that the photos would all turn brown from the sulphur content of the water – which would have been totally fine. What completely took me by surprise was the range of other colors that appeared: blues, aquas, yellows, greens, and crimsons.

I realized that along with sulfur, the water also contained a rich array of other dissolved elements – iron, calcium, aluminum, nickel – and these molecules would also bond to the silver, fusing and forming new compounds.

After doing this over and over again, I came to the realization that there are three mitigating factors that contribute to these colors:

- the acidity of the water

- the temperature of the water

- all of the different dissolved minerals and elements in the pool

The infinite variations between these four elements yields different colors and different spectrums. Two almost identical prints dipped in the same spring could yield wildly different results.

Nature makes the equation different – you're not in the darkroom, measuring by the milliliter and gram, but into the realm of uncertainty.

This is also one of the differences between the analog and digital photographic processes: no matter how hard you try to make analog works to be exactly alike, they will never be completely identical because they'll be different on a chemical level. The chemistry I used to create the photographs is slowly oxidizing over time, slowly getting diluted by the amount of prints I make. Even one second's difference in how long a print is bathed in a solution can make a huge difference way down the road when it's being placed in a hydrothermal system.

Looking at the examples, there is an amazing array of different colors: everything from the muted sepia tones you expected to really intense oranges and blues…

Generally, I found that the more dramatic and hostile to human life the spring is, the more interesting and dramatic the colors would be. So a thermal spring that one could bathe in would yield a more-or-less classical sepia tone, but a very acidic, boiling mudpot would yield very different, intense colors.

Over time, the acidity and presence of hydrogen sulfide will literally melt rock. So, often the ground around volcanic springs will consist of dissolved rock that has turned into clay, resulting in a brilliant array of colors. Walking around is almost like walking on a giant palette of thick impasto oil paint, which made this process feel so similar to painting.

It was like painting with the earth, and the minerals and the elements that are present right there in the landscape.

The work, which is the result of the very physical process of photochemistry, is also the result of a more immediate physical process: it looks like you had to develop creative ways to get the prints into the pools that you couldn't even get near.

I actually had a couple of more-or-less close calls where I very naively approached a spring and sank to my knees in this really colorful mud. It was fascinating but also really alarming, as the holes would immediately begin to fill with boiling mud. So I started improvising different ways to get my photos into pools that were too dangerous or too fragile to approach. One of them was using an old peanut butter jar that I found. I poked a set of holes in it to let the water in, loaded it with photos and stones to weigh it down, and attached a synthetic laundry line. This allowed me to throw photos into springs from a distance, and then reeling the jar back to examine the results - like a fisherman casting a line.

I enjoy the element of play in this work, the experimentation with chance and uncertainty. At its heart, it's about playing with mud and playing with water, and standing on shorelines and skipping stones.

Thermophile is on view in the Argus II Building (400 4th St., Ann Arbor) as part of the Stamps School of Art & Design's MFA Thesis Exhibitions. on display March 11 - April 2, 2016. The opening reception for the exhibition takes place on March 11 from 7:30 - 9:30 pm.

Learn more about Jon's work at jonverney.com.

Photos by Jon Verney; interview by Andre Grewe.